Contrary to some Christian pundits since the days of the Moral Majority, cultures seldom give up on having moral values. What they do is exchange one set of values for another. This is a poor trade when the new set of values is less concrete than the old set.

“Go to the gym every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at 7AM” is a better New Year’s resolution than “get in shape” because it’s something you might actually do in real life. Sadly, as Americans enter the third decade of the 21st century, the new set of values we’re adopting is as vague as any doomed January fitness kick.

Just before Christmas, the Wall Street Journal released a set of graphs. One of them tracks changes in how Americans rank a set of five values: patriotism, religion, having children, community involvement, and money.

Since 1998, the share of Americans describing patriotism, religion, and having children as “very important” has fallen by between ten and sixteen percent. Over the same period, the share of Americans who rate community involvement and money as “very important” has risen, in both cases by ten percent or more.

Let’s zero in on that last value: “community involvement.” It has a lot in common with the job title “community organizer,” which is to say I have no idea what either means. This is especially apparent given the bear market for patriotism (loving country), religion (loving God and neighbor), and children (those new, little people who replenish the other two categories).

If nation, church, and family aren’t the chief components that make up “community,” then what is? Wanting one but not the others is like wanting a beach without sand, sun, or salt water. It’s a purely theoretical beach, and any tan will be the result of the florescent lights as you sit at your computer trying to puzzle out what a community minus real people looks like, much less how to get involved in one.

If nation, church, and family aren’t the chief components that make up “community,” then what is? Wanting one but not the others is like wanting a beach without sand, sun, or salt water.

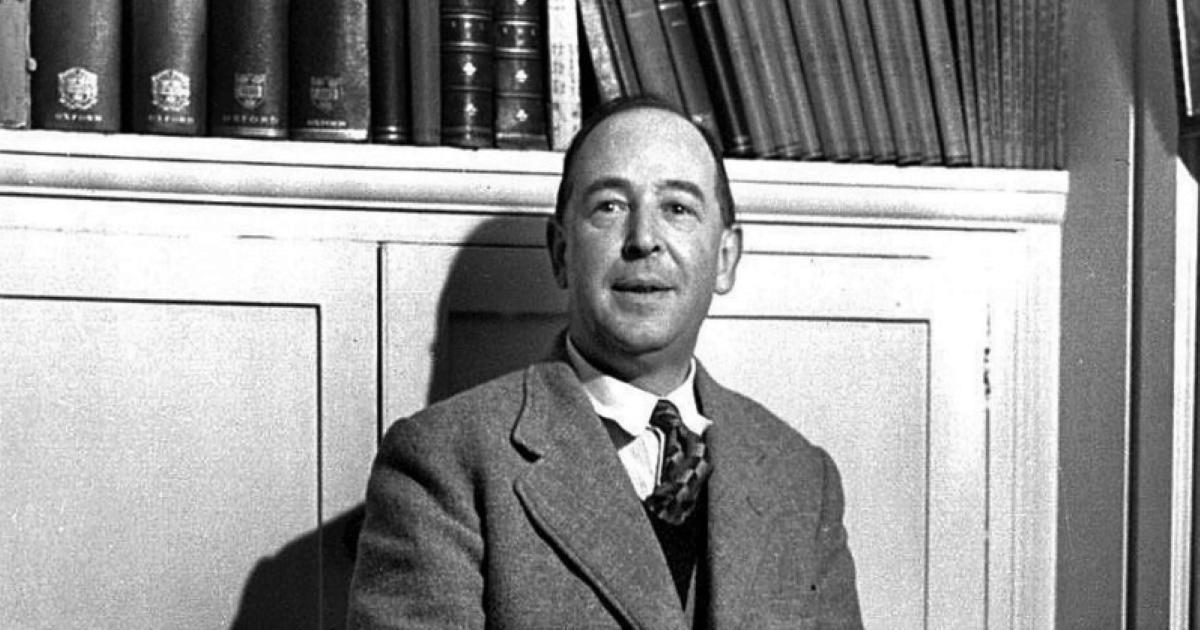

If a certain set of infernal telegrams intercepted by C. S. Lewis is any guide, this kind of hopeless ambiguity is the point for those making war on our souls. Writing to his nephew and understudy, veteran tempter Screwtape reveals a little secret about human beings: we are incurably idealistic.

“Do what you will,” he warns, “there is going to be some benevolence, as well as some malice, in your patient’s soul. The great thing is to direct the malice to his immediate neighbours whom he meets every day and thrust his benevolence out to the remote circumference, to people he does not know. The malice thus becomes wholly real and the benevolence largely imaginary.”

It is a fine thing to want to become involved with a community. But first we need to decide what we mean by “community,” beyond a talisman to keep away scarier, more ancient, less abstract words denoting groups of humans that might invite us over for the holidays.

Presumably Americans (especially the young among us) think ourselves noble for valuing “community involvement.” It sounds very progressive and eco-friendly. I picture it inscribed in muted hues of green and taupe with a “recyclable” symbol at the bottom. But we must get more concrete. We must talk about real people, not imaginary ones.

That’s largely why I find myself at the Colson Center, talking up values that—although articulated with more precision and theological depth (thanks, Chuck), sound an awful lot like the ideals the Moral Majority hawked when I was too young to vote (or even eat solid food).

“Community involvement” is very popular with my generation. Yet we know from loads of statistics that the only community many young Americans are consistently involved with barks and needs flea medication.

Likewise, there’s no shortage of articles announcing millennials’ departure from church and their failure to get married and form families. And overt love of country has become so tacky that the hipsters are now wearing t-shirts emblazoned with eagles and American flags—ironically, of course. We’re a generation lost in abstractions, in desperate need of uncool, unreconstructed, unrecyclable particularity.

Want to get in shape? Then pick a gym, buy a membership, and mark your calendar. Want to get involved in your community? Then for Heaven’s sake, join a church, start a family, and love the actual people of your city, county, state, and nation.

Want to get in shape? Then pick a gym, buy a membership, and mark your calendar. Want to get involved in your community? Then for Heaven’s sake, join a church, start a family, and love the actual people of your city, county, state, and nation.

It won’t always be glamorous. Unlike abstractions, realities are sharp-edged and like to argue with you, soil their diapers, and ask you to volunteer for nursery next Sunday. But reality is worth it all. It’s worth pouring your heart and soul and last breath into, if for no other reason than that it is real.

Screwtape’s slip, which is to say Lewis’ great insight, is that Hell doesn’t care how idealistic we are, or even whether our ideals are noble, so long as we never put them into practice. Indeed, “Jack” seemed to think hypocritical Pharisees with all their pomp and hollow professions make better sport for the devils below than any crook or carouser.

And that’s why in a culture that is struggling to define the ideal it holds highest, the most counter-cultural thing we can do is put that ideal into practice. Faraway people you will never meet won’t miss your noble sentiments. And you probably won’t miss that florescent tan. Like the real beach, real community beats the britches off the theoretical kind.

Image: C. S. Lewis, Google Images

Topics

C.S. Lewis

Christian Living

Christian Worldview

Community

Culture/Institutions

Human Nature

Relationships