The news this week about COVID-19, known as the coronavirus, has certainly, to understate it, escalated: New infections, grimmer projections, lots and lots of cancellations (including—can you believe it?—March Madness). The news changes so quickly day by day, even hour by hour, that it’s hard to keep up, much less know, really, what to think about all of this.

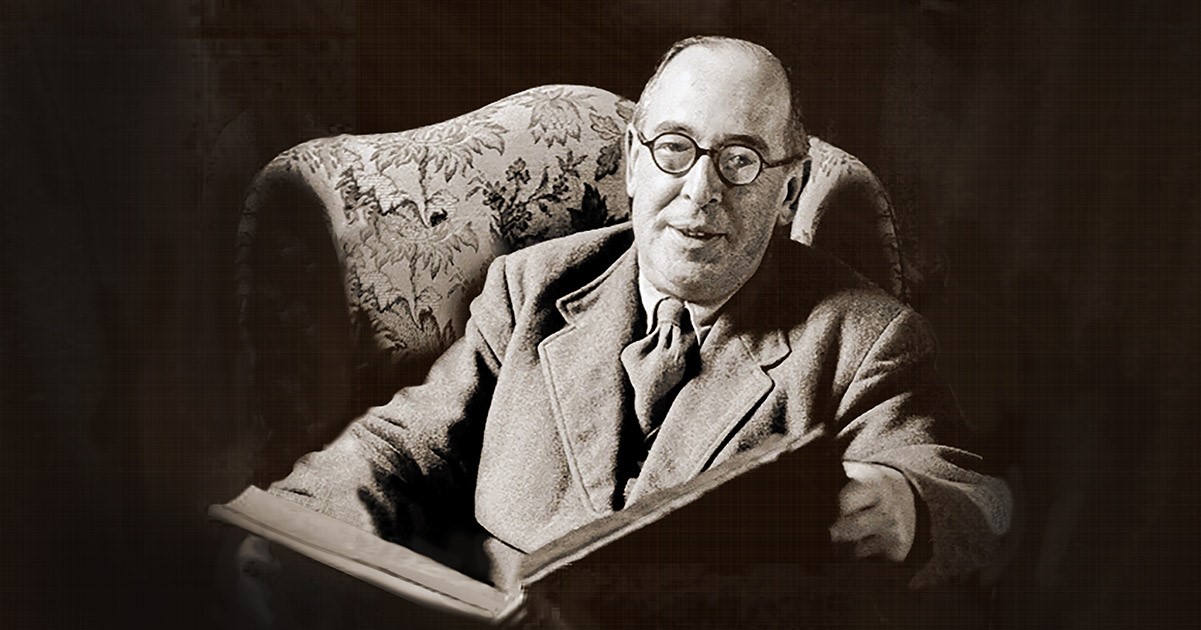

C.S. Lewis once said that we should read three old books for every new one. I think we should read three C.S. Lewis books for every new one. He never faced the coronavirus, of course, but in the late 1940s, the world was coming to grips with another threat: nuclear annihilation. The bomb was only a few years old, and in the hands of sworn national enemies. The uncertainty of what exactly could happen, not to mention what might happen, was palpable. In that context, C.S. Lewis wrote an essay entitled “On Living in an Atomic Age.”

I’m grateful to one of my BreakPoint colleagues, Ashlee Cowles, for reminding us of this essay along with some sage advice: Whenever you hear “atomic bomb” in this essay, think “coronavirus.”

“We think a great deal too much of the atomic bomb,” Lewis begins. To those who wonder how it’s possible to go on in the face of such a threat, Lewis recalls that theirs was not the first generation to live under a threatening shadow. In fact, if we’re honest, we all live under a sentence of death, and for some of us, that death could even be “unpleasant.”

The important question, says Lewis, is not whether or how we will die but if in the meantime we will be doing “sensible” and “human” things like “praying, working . . . reading, listening to music, bathing the children.”

Lewis asks his readers to consider the important but unsettling truth that “Nature does not, in the long run, favor life.” It’s an ominous observation that points to an essential worldview truth: “If Nature is all that exists—in other words, if there is no God and no life of some quite different sort somewhere outside of Nature—then all stories “will end in the same way: in a universe from which all life is banished without the hope of return.”

How do we respond to this unsettling truth? Lewis saw only three options: The first is suicide, something not uncommon in Britain of the 1940s and 50s. The second, “simply to have as good a time as possible. The universe is a universe of nonsense, but since you are here, grab what you can.”

Of course, as Lewis noted, “there is, on these terms, so very little left to grab—only the coarsest sensual pleasures.” Whether we’re talking about sex or listening to music, the pleasure is diminished by the knowledge that any enjoyment we might derive are merely “illusions,” the product of “irrational conditioning” determined by our genes.

The third response, Lewis said, is to “go down fighting,” to live as if the universe has meaning. We can insist on being rational and merciful even when the universe is not. Of course, if we choose that option, there’s no way to actually prevail against the “idiocy” of the universe—it would still win. Our insistence on being rational and merciful has no real justification.

The hopelessness of those three options should instead lead us to a different conclusion: “We must simply accept . . .,” said Lewis, “that we are spirits, free and rational beings, at present inhabiting an irrational universe, and must draw the conclusion that we are not derived from it.”

In other words, we must reject naturalism and embrace “a much earlier view:” biblical theism. It’s the only grounds on which we can avoid the despair brought on by the knowing that we are under a “sentence of death,” whatever form that death takes.

Lewis’ words are just as relevant today as they were seven decades ago. For people who believe there is a God, doing the “sensible” and “human” things are possible because we have hope. For those who don’t have that hope, no amount of toilet paper or cans of Spam stacked in the garage can make anyone truly safe, much less solve the ultimate question of meaning that haunts us all.

Today as yesterday, the world is still in God’s hands. Nothing has changed. Whatever the next chapter of this coronavirus story might be, the same questions remain to us: Will we trust God? And then, will we love our neighbors? And finally, how shall we then live?

Topics

Apologetics

C.S. Lewis

Christian Living

Christian Worldview

Creation

Health & Science

History

Religion & Society

Theology

Worldview

Resources:

Have a Follow-up Question?

Up

Next

Related Content

© Copyright 2020, All Rights Reserved.