God vs. Child Sacrifice

The God of Abraham Is a Very Different God

03/21/19

John Stonestreet

Recently, archaeologists working in northern Peru made a discovery they called “disturbing and disquieting.”

Digging in the outskirts of the pre-Columbian city of Chan-Chan, they found the remains of about 140 children and 200 animals, mostly llamas. The condition of the children’s remains made it clear that they had been sacrificed along with the animals, perhaps in response to some emergency or dire threat. According to the Washington Post, it’s the site of “the largest known child sacrifice in the world.”

While this is a very unpleasant subject, it serves as a gruesome reminder of how biblical religion, especially Christianity, changed the course of human history.

Chan-Chan was the capital of the Chimú empire. Before their disturbing find, the archaeologists were not aware that this ancient people practiced child sacrifice. Their hypothesis is that the sacrifices were in response to a severe weather event, perhaps a strong El Niño, which caused catastrophic flooding.

Whatever precipitated the child sacrifice, the Chimú were far from alone in their attempts to placate the gods by slaughtering their children. Their conquerors, the Incan Empire, also practiced child sacrifice in times of emergency.

In the Old World, the Carthaginians, who were descended from the biblical city of Tyre, sacrificed children to their gods at shrines the Hebrew Bible called “tophets.” The Romans made a big deal out of this fact in their anti-Carthaginian propaganda, conveniently omitting the fact that they did the same in response to the Carthaginian general Hannibal’s invasion of Italy.

The Carthaginians weren’t the only ancient people who emulated Canaanite child sacrifice. Pre-exilic Israel practiced this demonic rite, as well. In Jeremiah 7, the Lord denounces the “high place of Topheth” where the people “burn their sons and daughters in the fire.”

On account of this abomination, the Lord said that “I cause to cease from the cities of Judah, and from the streets of Jerusalem, the voice of mirth and the voice of gladness, the voice of the bridegroom and the voice of the bride; for the land shall become a waste.”

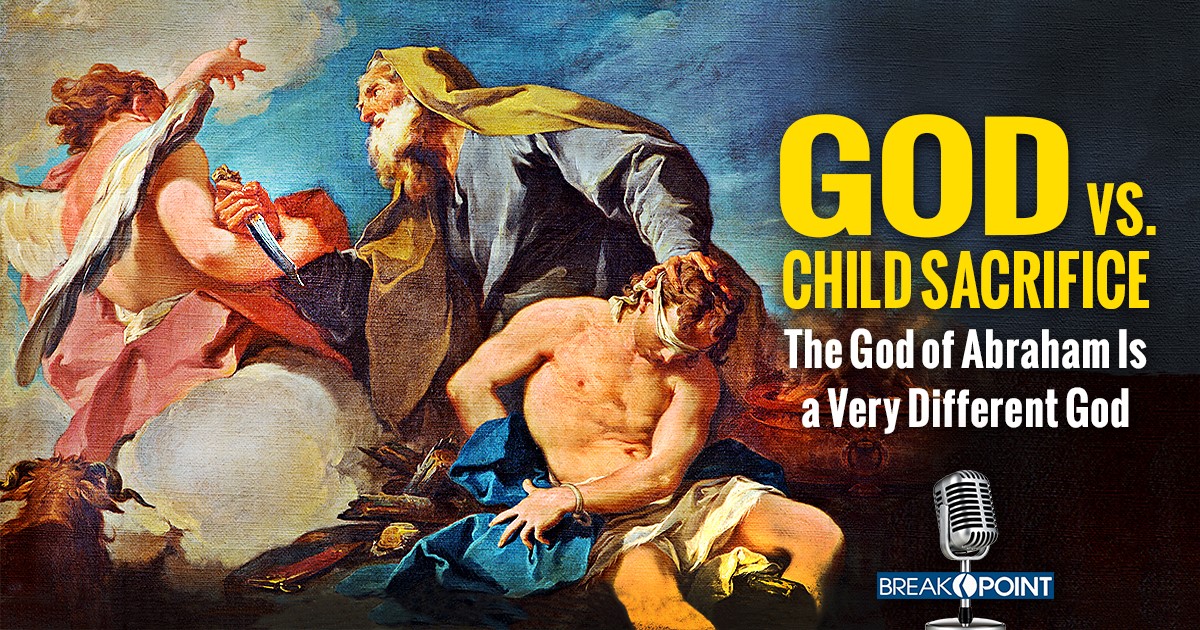

Then, of course, there’s that one specific example cited by the Washington Post in its article about the find in Peru: the “Binding of Isaac” in Genesis 22. While parts of this story are perplexing and even troubling, it’s inclusion along with the other examples misses a crucial point: There was never a chance Isaac would be sacrificed.

If Abraham, to quote Bob Dylan’s paraphrase, had replied to God “Man, you must be putting me on,” Isaac lives. If, as actually happened, Abraham was willing to be fully obedient to God’s instruction, Isaac lives because God prevents the sacrifice.

Jewish Rabbis have long taught that this story of Abraham and Isaac condemns the practice of child sacrifice, especially in light of the repeated subsequent condemnations of the practice throughout the Old Testament. It was part of Abraham’s coming to understand that the God who’d called him to leave his homeland was a very different God than the gods he left behind.

This God, as Christianity would later teach the world, doesn’t demand our children as a sacrifice, but rather sacrificed His own Son on our behalf.

In fact, early Christians took the Jewish prohibition on child sacrifice and extended it to cover contemporary Roman practices such as abortion and infanticide. Ultimately, it’s because of Christianity’s clarity on the killing of children that we find the discovery at Chan-Chan so chilling today, despite our own culture’s embrace of moral relativism.

Chilled or not, we still fail to see the obvious parallels between what happened at Chan-Chan and recently-enacted laws that permit the killing of infants who could easily survive outside the womb. Just as biblical religion made the world a far safer place for young children, the decline of Christian influence over our culture threatens to reverse the moral progress we’ve made since the ancient world.

It may be that future archaeologists, as they dig through the remains of our civilization, will find themselves disturbed and disquieted, too.

Have a Follow-up Question?

Related Content

© Copyright 2020, All Rights Reserved.