What We’re Missing About Mass Shootings

Our society largely fails to cultivate young men, to teach them about their fallen natures, and to morally form them to choose love over hate and courage over violence.

11/23/22

John Stonestreet

Last Saturday, at around midnight, a 22-year-old man entered a Colorado Springs nightclub with an assault-style weapon and started firing. Five people were killed and 18 injured in the evil attack that lasted only minutes before Army veteran Richard Fierro heroically charged and subdued the attacker, with help from a few others. Our city mourns the loss of these people made in the image of God, and we now reckon with the shattering of peace and community as the holiday season approaches.

Media outlets were quick to mention, often with an accusatory tone, that the nightclub is an LGBTQ+ establishment in a city brimming with evangelical ministries that teach homosexual behavior is sinful. Many were quick to imply the shooting was motivated by hatred of people who identify as LGBTQ. That may or may not be true. If it is, the guilt for the hatred and evil actions of the shooter is not shared by the millions who hold moral views about sex, marriage, and gender, whether faith-based or not.

Even as details of this particular tragedy continue to emerge, America, the city of Colorado Springs, and the state of Colorado are left to reckon with yet another mass shooting. The sheer number of which demands that we ought not isolate each from the others, as if there are no patterns or trends that connect them all. There are, but they are not the narratives to which the various sides so quickly retreat, such as political affiliation, religious affiliation, or a particularly targeted community.

Writing a few years ago at the LA Times, professor of criminology Jillian Peterson and sociologist James Densley offered a revealing look at America’s mass shooters. They studied every shooter since 1966, and the vast majority have four things in common: “early childhood trauma and exposure to violence at a young age”; seeking “validation” in extreme communities, often online; openly admiring the work of prior shooters; and nearly all are longtime loners with an identifiable “crisis point,” like getting fired or expelled from school. Oh, and by the way, they are all men.

In fact, the young men who appear on CNN’s list of the “27 Deadliest Mass Shootings in U.S. History” have something else in common: Almost all of them grew up without fathers. Early indications suggest the same was true of the Colorado Springs shooter.

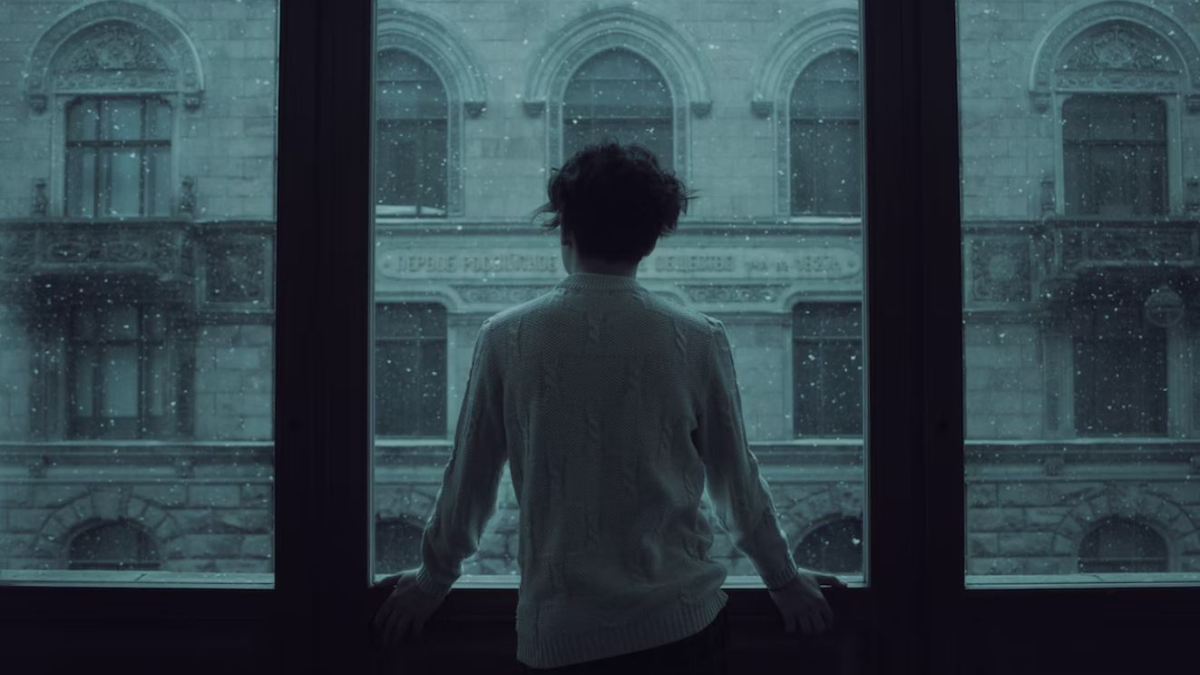

Put differently, with few exceptions, the signs that a young man is headed down a dark road overlap noticeably with signs we see across our culture that young men in general are not doing well. Lacking strong role models and healthy social groups, increasingly left behind academically and vocationally, and floundering for a purpose in life beyond video games, countless males have sought solace in the only communities they can find—usually online—where the foulest kinds of hate, conspiracy theories, and nihilism await them.

Of course, these factors don’t always lead one to become a mass shooter. Our broken culture may have encouraged them along dark paths, but they made the choice to walk that way, and they bear the guilt themselves. Even so, for every young man who is catechized into some toxic radicalism (like Dylann Roof or the El Paso shooter) or into nihilistic unbelief (like Dylan Klebold, Eric Harris, and the Aurora theater shooter), and then chooses to act on it with a gun, there are millions of others who do not.

Still, that doesn’t mean they’re doing well either. Quite the opposite: Our society largely fails to cultivate young men, to teach them about their fallen natures, and to morally form them to choose love over hate and courage over violence. Thus, the epidemics of addiction, aimlessness, depression, irresponsibility, perversion, selfishness, victimhood, and low expectations continue.

Until we face the fact that the root of our problem lies here, the fruit will continue to be bitter. Unless we rebuild the institutions of civil society that cultivate young men—especially the family—there is no way forward.

We certainly won’t fix this problem through government policies or mindless distractions. As you look across the scope of culture, it seems as if there’s only one option left: The Church, with its kingdom vision and distributed workforce, has the necessary resources to target young men with truth, forgiveness, accountability, meaning, and hope.

Have a Follow-up Question?

Related Content

© Copyright 2020, All Rights Reserved.