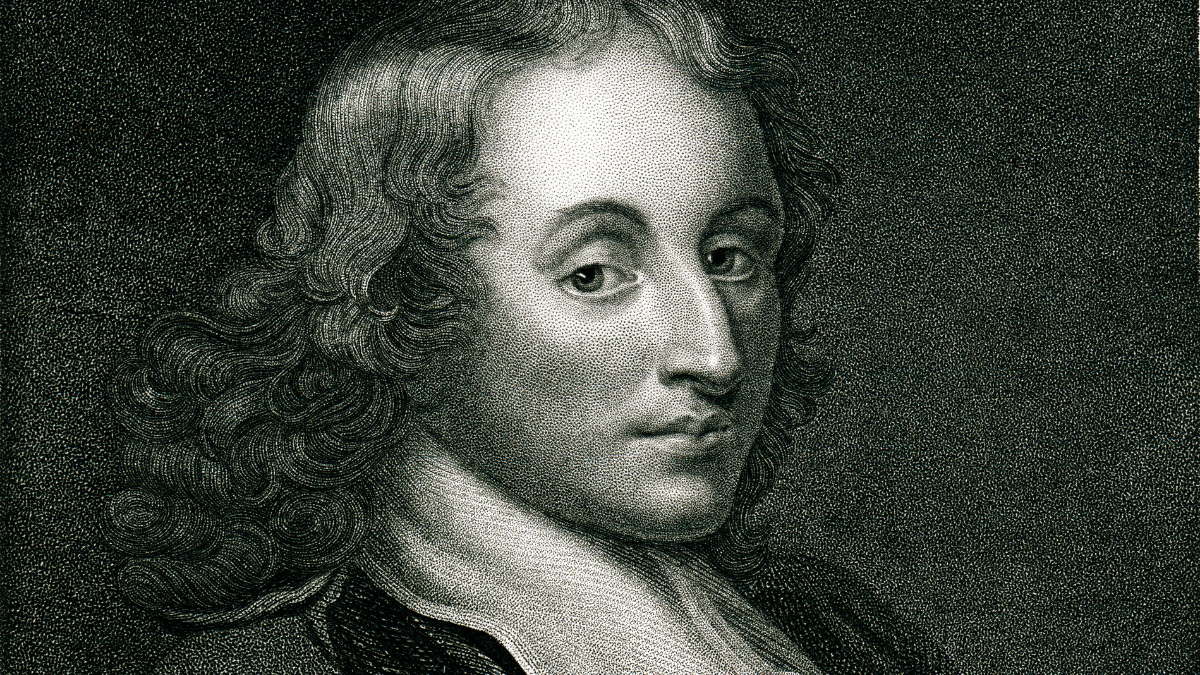

The Life, Faith, and Brilliance of Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal’s intellect, passion, and eloquence have lost none of their fire, dedicated as they were to the God who claimed his total devotion.

08/18/23

John Stonestreet Kasey Leander

On August 19, 1662, French philosopher, mathematician, and apologist Blaise Pascal died at just 39 years old. Pascal, despite his shortened life, is renowned for pioneering work in geometry, physics, and probability theory. His most powerful legacy, however, involves the ways he engaged with life’s biggest questions.

Pascal’s intellect garnered attention at an early age. At 16, he produced an essay on the geometry of cones so impressive that René Descartes initially refused to believe it could possibly be attributed to a “sixteen-year-old child.” Later, Pascal advanced the study of vacuums in the face of a prevailing (and misplaced) belief that nature is completely filled with matter, and thus “abhors a vacuum.”

In 1654, his work on probability took a new turn when he was sent a brainteaser by a friend. Applying mathematics to the problem, Pascal laid out rows of numbers in a triangle formation, a formation that now bears his name. As author John F. Ross described,

Here was the very idea of probability: establishing the numerical odds of a future event with mathematical precision. Remarkably, no one else had cracked the puzzle of probability before, although the Greeks and Romans had come close.

In 1646, Blaise Pascal encountered the kindness of two Jansenist Christians caring for his injured father. Their love in action earned Pascal’s admiration. Then, on the evening of November 23, 1654, Pascal experienced God’s presence in a new and personal way, which he described on a scrap of parchment that he sewed into his jacket and carried with him for the rest of his life:

FIRE—God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of the philosophers and scholars. Certitude, certitude. Heartfelt joy, peace. God of Jesus Christ. My God and thy God. Thy God shall be my God.

In his writing, Pascal’s notions of probability met his faith in God. A compilation of his collected manuscripts was published after his death in a volume entitled, Pensées, or “Thoughts.” Best known is his famous “wager” that, facing uncertainty and in a game with such high stakes, it makes far more sense for fallen human beings to believe in God’s existence than doubt it. “If you gain,” he wrote, “you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation that He is.”

Pascal also offered among the keenest diagnoses of humanity:

The human being is only a reed, the most feeble in nature; but this is a thinking reed. It isn’t necessary for the entire universe to arm itself in order to crush him; a whiff of vapor, a taste of water, suffices to kill him. But when the universe crushes him, the human being becomes still more noble than that which kills him, because he knows that he is dying, and the advantage that the universe has over him. The universe, it does not have a clue.

Or, even better:

What a Chimera is man! What a novelty, a monster, a chaos, a contradiction, a prodigy! Judge of all things, an imbecile worm; depository of truth, and sewer of error and doubt; the glory and refuse of the universe.

He also described our moral conditions as human beings, “[W]e hate truth and those who tell it [to] us, and … we like them to be deceived in our favour” (Pensées 100).

Apart from God, Pascal observed, people distract themselves from the reality of death. But the diversions run out, and then mankind

feels his nothingness, his forlornness, his insufficiency, his dependence, his weakness, his emptiness. There will immediately arise from the depth of his heart weariness, gloom, sadness, fretfulness, vexation, despair. (Pensées 131)

“Between us and heaven or hell there is only life, which is the frailest thing in the world” (Pensées 213 ).

With a poetic nod to his work on vacuums, Pascal concluded:

What is it then that this desire and this inability proclaim to us, but that there was once in man a true happiness of which there now remain to him only the mark and empty trace …? But these are all inadequate, because the infinite abyss can only be filled by an infinite and immutable object, that is to say, only by God Himself.

A generation later, as waves of the Enlightenment swept over Europe, the continent’s most prominent thinkers could not escape Pascal’s brilliance. According to philosopher Dr. Patrick Riley,

Holbach, as late as the 1770s, still found it necessary to quarrel with the author of the Pensées, Condorcet, when editing Pascal’s works, renewed the old debate; Voltaire throughout his life, and even in his last year, launched sally after sally at the writer who frightened him every time he—a hypochondriac—felt ill.

On the human condition in particular, the French Revolution would prove Pascal right and Voltaire wrong. Divorced from God and instead committed to the worship of “pure reason,” France devolved into a violent, anarchic wasteland.

Even today, Blaise Pascal’s intellect, passion, and eloquence have lost none of their fire, dedicated as they were to the God who claimed his total devotion. As he wrote on the parchment sewn into his jacket,

Jesus Christ.

I have fallen away: I have fled from Him,

denied Him, crucified him.

May I not fall away forever.

We keep hold of him only by the ways taught in the Gospel.

Renunciation, total and sweet.

Total submission to Jesus Christ and to my director.

Eternally in joy for a day’s exercise on earth.

I will not forget Thy word. Amen.

This Breakpoint was co-authored by Kasey Leander. If you enjoy Breakpoint, leave a review on your favorite podcast app. For more resources to live like a Christian in this cultural moment, go to breakpoint.org.

Have a Follow-up Question?

Related Content

© Copyright 2020, All Rights Reserved.