“It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but just as much to stand up to our friends.” – Professor Dumbledore

This nugget from Harry Potter materialized in my mind recently after I saw the new movie, “Bombshell.” As you may know, the film tells the now-infamous story of Roger Ailes who used his position as CEO of FOX News to sexually harass young women eager to build a platform with the FOX audience.

While the movie was, to be sure, thought provoking, I left the theater thinking less about it and more about a quip from a stranger I heard on the way out:

“Too bad the people who really need to see this movie wouldn’t be caught dead buying the ticket.”

The implication was that we—the good guys—had just seen the dirty laundry of them—the bad guys. We—those who were in on the joke vis-à-vis FOX—weren’t the ones who needed to be reminded of sexual exploitation. It’s the stodgy old conservatives, they are the ones who really need the message. Too bad they’ll never see it.

Pot, meet kettle.

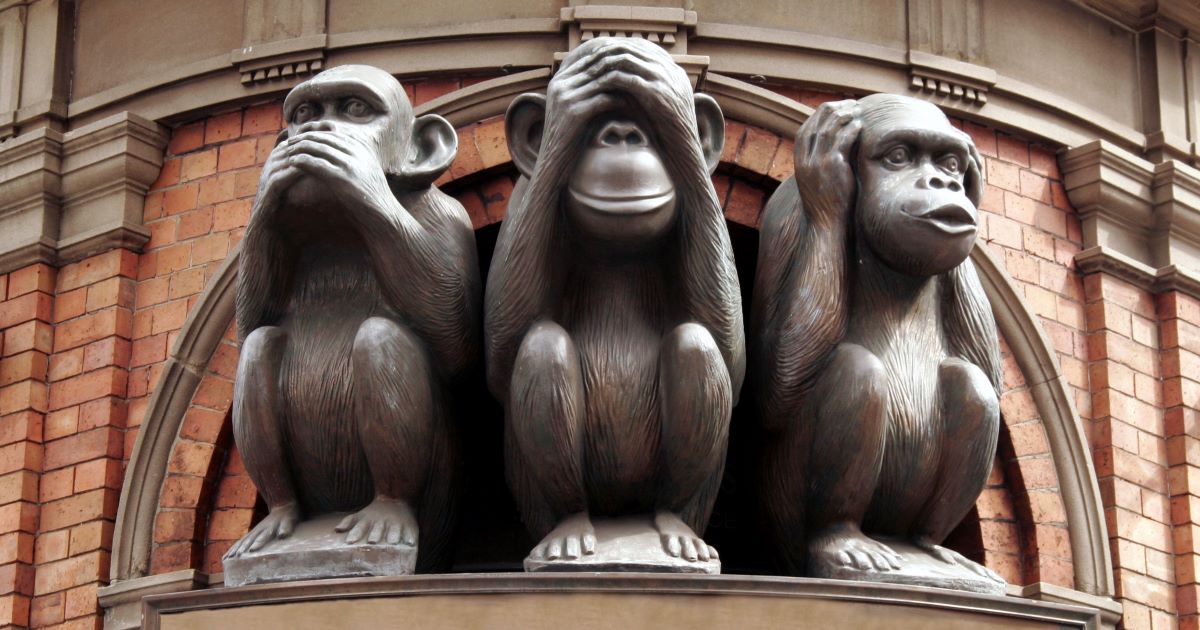

Finding the faults in others is easy, very easy. Seeing it in ourselves, in our own “team,” that’s the challenge. Yet, the surest way to create a culture where we turn a blind eye to evil around us is to allow our tribal narratives to so calcify our perceptions that we simply can’t account for villainy within our own ranks.

I’ve always been struck the observation made by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn:

“If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either, but right through every human heart, and through all human hearts.”

Finding the faults in others is easy, very easy. Seeing it in ourselves, in our own “team,” that’s the challenge.

If the laudable goals of things like the #MeToo movement are to be realized, we have to escape these tribal tendencies to view our side as always good and the other as always bad. This isn’t to say that we can’t call out bad actors on the other side, but we can’t do it at the expense of the much harder calling of addressing the problems on our own side.

To be sure, recognizing and naming the fault in the other isn’t wrong, but neither is it enough if one’s goal is to tackle the complex evils in society. Achieving such an aim will require that work for which our tribal age has not well prepared us—seeing and naming the fault in our own side.

You can see a similarly calcified narrative in Netflix’s “The Two Popes,” a movie which contrasts the conservatism of Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict) with the purported progressivism of Jorge Mario Bergoglio (Pope Francis).

Whether it was laziness or duplicity on the part of the screenwriter, in addressing the sex abuse crisis of the Church the movie makes it seems as if the hands of Benedict were dirty as he left Vatican City and Bergoglio’s were spotless as he entered.

The truth, as Irish playwright John Waters pointed out, is not so simple—and, in many ways, quite to the contrary. The problem isn’t that the film pointed out sins in Benedict’s past, the problem was that their simple good/bad narrative couldn’t account for Bergoglio’s.

The tribal reasoning was thinly veiled: Benedict never budged on the Catholic church’s teaching on sexual ethics, therefore he must be bad. Francis has questioned the doctrine of hell; therefore, he must be good.

Both “The Two Popes” and “Bombshell” gave their audience the medicine that there are predators in the world but helped it go down with the spoon full of sugar that those predators exist in neat categories quite apart from us.

[W]e have to escape these tribal tendencies to view our side as always good and the other as always bad. This isn’t to say that we can’t call out bad actors on the other side, but we can’t do it at the expense of the much harder calling of addressing the problems on our own side.

A story that’s not nearly as well-known as it should be can help point us in a better direction, and it so happens to involve the former managing editor of FOX News, Brit Hume.

In 1971, Hume was working as a researcher for the acclaimed conservative columnist Jack Anderson. In that capacity, Hume learned that Al Capp—a cartoonist, writer, and speaker well-connected in the conservative world—was serially abusing young women on college campuses at which he spoke.

The abuse was, apparently, well known by various university officials and summarily swept under the rug. Through his investigation, Hume—a young, relatively inexperienced journalist—nearly singlehandedly brought to justice a man with whom, it should be noted, he had every incentive not to quarrel.

You see, Hume had to have known that exposing Capp would bring down one of their careers—Capp’s or his own. Indeed, after the article went to print it raised the ire of everyone from the Washington Post, who refused to run the story, to the White House, where Nixon employed the aid of his yet-to-be-converted “fixer” Chuck Colson to make the fuss go away.

Yet, Hume and Anderson stood by the reporting because it was the right thing to do. Because they hated sexual predation more than they cherished their own side’s reputation. Because scoring points and getting ahead isn’t everything.

While that anecdote may seem old to our world’s “what’s new, what’s next” mentality, we must remember that there remain people today willing to address the compromise and complicity of their own side (one thinks of the valiant efforts of Rachael Denhollander in addressing the abuse of the evangelical community of which she’s a part). While such examples of Dumbledorian heroism are few and far between in our tribal moment, they should be celebrated and lauded when they do occur.

In an age in which we’re so tempted to reserve admiration and forgiveness for our particular tribe alone, it would be wise of us to practice that lost civic virtue of honesty, which forces us to look with charity on the other even as we look with scrupulosity on ourselves.

Dustin Messer teaches theology at Legacy Christian Academy in Frisco, TX and ministers to young adults at All Saints Dallas. He’s the author of the forthcoming book, “Be Ye Kind: Convictional Civility in a Combative Culture.”