BreakPoint

BreakPoint: Remembering Tiananmen Square

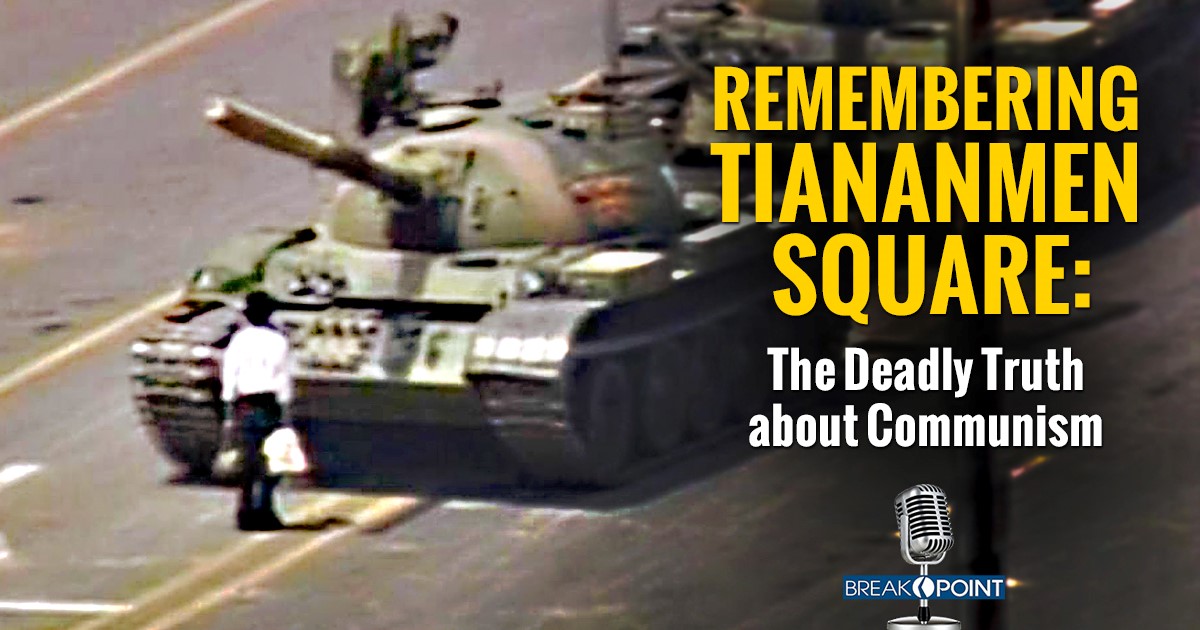

For two months in 1989, students gathered in Tiananmen Square demanding political reforms analogous to the economic reforms instituted by then-Chairman Deng Xiaoping.

After some initial indecision, the Communist Party decided to crack down. On May 20th, the government declared martial law and moved 250,000 troops into Beijing. On June 3rd, state-run television warned Beijing residents to stay inside.

The next day, the army advanced toward Tiananmen Square. Protesters attempted to impede the army’s advance and destroyed more than 100 military vehicles, and damaged nearly 500 others.

But ultimately resistance would prove to be futile. Trucks and armored personnel carriers joined tanks and attack helicopters. The army’s principal target was a 10-meter tall statue dubbed the “Goddess of Democracy,” which was erected by the students and bore a more-than-passing resemblance to the Statue of Liberty.

After first firing warning shots, the troops fired directly on the protesters. Estimates of the death toll range widely, from hundreds to thousands. In addition, at least 1,600 people were arrested, many imprisoned for more than two decades, and others who were never seen again.

The message from the Communist Party was clear: To be rich might be, as Deng once put it, “glorious,” but forget about being free. The events of June 1989 made clear that the Communist Party was determined to retain complete political and social control.

Given this history with this regime, no one should be surprised at the recent crackdown on Chinese Christians and Muslim Uighurs.

But what is surprising is how many Chinese today are untroubled by the events of June 1989. Even worse, the authors of a recent article in the Washington Post described a popular nostalgia for Mao Zedong. Mao’s rule was among the most brutal in all of history.

This is the Mao whose attempt to industrialize and collectivize China virtually overnight—called the “Great Leap Forward”—killed “at least 45 million people.” This is the Mao whose “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” attempted to purge Chinese society of capitalist and traditional elements by killing between 500 thousand and 3 million people, and sending countless more into internal exile. Among its victims were the father and aunt of current leader Xi Jinping, who committed suicide as a result of being persecuted.

The tragic irony is that any nostalgia for Mao only helps legitimize the authoritarianism and oppression now expanding under Xi.

How can we make sense of this selective and misguided historical memory? Most of the nostalgic are too young to have personally experienced Mao’s rule. Even more, they haven’t been taught the truth about Mao or Tiananmen at state-approved or state-run schools.

Of course, that same thing can’t be said of us in the West, whose memory is just as selective and just as wrong when it comes to communism. Writer Cathy Young, who lived in the USSR until she was 17, describes what she calls “Commie Chic.” She’s not referring to Soviet apologists or sympathizers prior to 1991.

She’s talking about a 2018 Teen Vogue article that urged readers to use Karl Marx’s ideas to understand how Donald Trump was elected president. She’s referring to a 2017 New York Times op-ed insisting that women had better sex in communist East Germany. Or one hard-left publication that recently tweeted “For all the Soviet Union’s many faults, by traversing its vast architectural landscape, we can get a glimpse of what a built environment for the many, not the few, could look like.”

Now if all we knew about communism were its history of oppression and mass murder, that should be enough to disavow us of any nostalgia for it. As the authors of the “Black Book of Communism” wrote, “Communist regimes turned mass crime into a full-blown system of government.” The result was 100 million-plus deaths, including the martyrs of Tiananmen Square.

But that tweet itself about building environments for the many, not the few, tells us all we need to know about the flawed worldview that undergirds this great historical evil. To a communist, the society is always more important than the individual. Individuals must be sacrificed for the utopian and fantastical ‘greater good’ that lies somewhere in the future and always just beyond reach.

Whenever it’s tried, in the past or in the future, this fatal flaw will leave fatalities, because bad ideas have victims.

The history of communism, like its worldview, is neither glorious nor worthy of nostalgia.

Download mp3 audio here.

For two months in 1989, students gathered in Tiananmen Square demanding political reforms analogous to the economic reforms instituted by then-Chairman Deng Xiaoping.

After some initial indecision, the Communist Party decided to crack down. On May 20th, the government declared martial law and moved 250,000 troops into Beijing. On June 3rd, state-run television warned Beijing residents to stay inside.

The next day, the army advanced toward Tiananmen Square. Protesters attempted to impede the army’s advance and destroyed more than 100 military vehicles, and damaged nearly 500 others.

But ultimately resistance would prove to be futile. Trucks and armored personnel carriers joined tanks and attack helicopters. The army’s principal target was a 10-meter tall statue dubbed the “Goddess of Democracy,” which was erected by the students and bore a more-than-passing resemblance to the Statue of Liberty.

After first firing warning shots, the troops fired directly on the protesters. Estimates of the death toll range widely, from hundreds to thousands. In addition, at least 1,600 people were arrested, many imprisoned for more than two decades, and others who were never seen again.

The message from the Communist Party was clear: To be rich might be, as Deng once put it, “glorious,” but forget about being free. The events of June 1989 made clear that the Communist Party was determined to retain complete political and social control.

Given this history with this regime, no one should be surprised at the recent crackdown on Chinese Christians and Muslim Uighurs.

But what is surprising is how many Chinese today are untroubled by the events of June 1989. Even worse, the authors of a recent article in the Washington Post described a popular nostalgia for Mao Zedong. Mao’s rule was among the most brutal in all of history.

This is the Mao whose attempt to industrialize and collectivize China virtually overnight—called the “Great Leap Forward”—killed “at least 45 million people.” This is the Mao whose “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” attempted to purge Chinese society of capitalist and traditional elements by killing between 500 thousand and 3 million people, and sending countless more into internal exile. Among its victims were the father and aunt of current leader Xi Jinping, who committed suicide as a result of being persecuted.

The tragic irony is that any nostalgia for Mao only helps legitimize the authoritarianism and oppression now expanding under Xi.

How can we make sense of this selective and misguided historical memory? Most of the nostalgic are too young to have personally experienced Mao’s rule. Even more, they haven’t been taught the truth about Mao or Tiananmen at state-approved or state-run schools.

Of course, that same thing can’t be said of us in the West, whose memory is just as selective and just as wrong when it comes to communism. Writer Cathy Young, who lived in the USSR until she was 17, describes what she calls “Commie Chic.” She’s not referring to Soviet apologists or sympathizers prior to 1991.

She’s talking about a 2018 Teen Vogue article that urged readers to use Karl Marx’s ideas to understand how Donald Trump was elected president. She’s referring to a 2017 New York Times op-ed insisting that women had better sex in communist East Germany. Or one hard-left publication that recently tweeted “For all the Soviet Union’s many faults, by traversing its vast architectural landscape, we can get a glimpse of what a built environment for the many, not the few, could look like.”

Now if all we knew about communism were its history of oppression and mass murder, that should be enough to disavow us of any nostalgia for it. As the authors of the “Black Book of Communism” wrote, “Communist regimes turned mass crime into a full-blown system of government.” The result was 100 million-plus deaths, including the martyrs of Tiananmen Square.

But that tweet itself about building environments for the many, not the few, tells us all we need to know about the flawed worldview that undergirds this great historical evil. To a communist, the society is always more important than the individual. Individuals must be sacrificed for the utopian and fantastical ‘greater good’ that lies somewhere in the future and always just beyond reach.

Whenever it’s tried, in the past or in the future, this fatal flaw will leave fatalities, because bad ideas have victims.

The history of communism, like its worldview, is neither glorious nor worthy of nostalgia.

Download mp3 audio here.

06/4/19