And behold, a lawyer stood up to put him to the test, saying, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” He said to him, “What is written in the Law? How do you read it?” And he answered, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” And he said to him, “You have answered correctly; do this, and you will live. But he, desiring to justify himself, said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” – Luke 10:25-29

Christians of all stripes give their hearty assent to Christ’s call to love our neighbors; we’re rather less united when it comes to putting that love into practice. At least we think we’re disunited. Very different Christians make the very same mistake in very different ways when trying to follow Christ’s command.

Progressives cry that the church must provide for the downtrodden because they deserve it and care for the outcast because they’ve been oppressed. Traditionalists counter that we must be cautious not to endanger ourselves or to enable the immoral in their sin. Both assume that the worthiness of the recipient determines the appropriateness of our love.

Christ’s call to love our neighbor puts the lie to both of these errors. God’s love for us show us that we ought to act in love to all, regardless of whether we think they deserve it or not.

For many people, both Christian and non, Jesus’ call to “Love your neighbor” is the essence of Christianity. Combined with His call not to judge others, this is for many the shorthand version of Christian ethics. As straightforward as this seems, there’s a problem. When narrowed down to a catchphrase, the simplistic call to “Love your Neighbor,” can yield something which is not un-Christian but is, in a way, sub-Christian.

Now, don’t get me wrong. There are far worse places to root your morality than this. But, while Christ’s words clearly govern our behavior towards all people in a self-giving and self-denying love, many reduce this neighbor love to mere sentiment and strip away its radical nature.

There’s just nothing particularly Christian about loving nice people. Anyone can love nice people. Loving them is a piece of cake. Loving difficult people is, well, difficult.

There’s just nothing particularly Christian about loving nice people. Anyone can love nice people. Loving them is a piece of cake. Loving difficult people is, well, difficult. The love which Christ calls us to exhibit is not just the love for nice people, for easy people, for non-threatening people of whom you are not afraid. No, Jesus calls us to love the hostile, difficult, and genuinely dangerous people in our lives.

When we read the account of the Good Samaritan, we see God calling us to an uncomfortable love, a love that is not supposed make us feel good about ourselves, a love that doesn’t deny the troubles of loving others. Instead, it calls on us to love others with the same gloriously undeserved love which God has shown to us.

This tale is one of those stories like Noah’s Ark and Jonah and the Whale which is well-known enough that it has passed into the popular imagination. People with absolutely no understanding or even respect for Christianity will readily refer to so-and-so being a Good Samaritan. Some local and state governments have enacted what they call Good Samaritan laws which govern the way we are to act when we encounter people in emergency situations.

Now, any child in Sunday School knows that Jews and Samaritans did not get along. We don’t normally get much beyond that, but we need to remember that this animosity was no small thing. These two groups hated each other’s guts, and they had been hating each other for centuries.

Certainly, ethnic strife played its role, but there was more going on that hatred for the “other.” They’d each given just cause to see the other not just as different but as an outright enemy. During the latter part of the Old Testament and in the Greco-Roman period which followed, Jews attacked Samaritans and Samaritans attacked Jews. These neighboring nations did not like one another and regularly offered reasons for this hatred to endure. This was no fear of the unknown; this was a pathos against the all too well known.

When Jesus is calling on you to love your neighbor, He is saying for you to love this neighbor. This neighbor you hate, this neighbor you fear. That guy. Love him.

We can miss the radical nature of this love when our focus centers on the supposed virtue of the neighbor as the reason for loving him. For some of us the temptation is to ask for confirmation of the neighbor’s goodness before we will grant him our love. Will the person misuse our generosity? Will my kindness only serve to inflate an already enlarged ego?

We ask, is this a safe person? Is this someone who will harm me? These are fair questions, but this story doesn’t let us let that be the deciding factor. Was the man left injured on the road a safe man? A good man? We don’t know, but we are told through the Samaritan’s example to love such people regardless of their righteousness. Our love for our neighbors is not to wait upon their moral improvement before this love can be shown.

Another way we miss this is somewhat more dangerous because it is more subtle. We sometimes misunderstand Christ’s words here, at least in practice, because we assume the goodness of those we love. We are so convinced to care for the needy, to care for our victimized neighbors, that we tell ourselves that these neighbors are good.

We tell ourselves and others that the homeless man begging for money is the victim of a heartless socio-economic system, not an alcoholic who is abusing the system, that the homosexual or transgender person just wants to love like the rest of us and is not someone violating the testimony of nature and nature’s God, that the young man fleeing from the war torn Middle East or Latin America is just looking for a way to live his life in peace, not someone who could turn the wealth and freedom of the West against it. Would that it were always so! Loving people like this is easy. Loving people like this is loving lovable people, likable people. But God calls us to more.

We aren’t to love our neighbors because we’re that good. We aren’t to love our neighbors because they’re that good. We are to love our neighbors because God is that good.

Again, ask yourself, was the man left on the road a good man? A worthy man? A lovable man? We don’t know. We do know that he was an enemy to the Samaritan. Did the Samaritan help him because he wasn’t afraid or believed in his heart that victims couldn’t also be villains? No. He helped this man, this enemy, without knowing whether he deserved it.

Christ is saying that to love your neighbor as yourself, to follow the law of God, means that you will give this love to the people around you in need even if you are afraid, even if you think they might be unrighteous, even if you know them to be an enemy. This is radical love. This is Christian love. This is a love given by those who are unworthy to those who are unworthy on account of the One who is worthy of all.

We aren’t to love our neighbors because we’re that good. We aren’t to love our neighbors because they’re that good. We are to love our neighbors because God is that good.

If it’s about you, then you only have to love so far as to feel good about yourself and when you feel you are not in any danger. Likewise, if it is about your neighbor, then you only have to love them if they deserve it and if they pose no threat to anyone. Loving others for ourselves leaves us free to hate anyone inconvenient. Anyone can do that. Loving others for themselves leaves us free to judge the worth of others. Anyone can do that. Having a biblical, theocentric love of neighbor frees us from either temptation. It isn’t about our glory or their goodness, but about glorifying the One who is goodness epitomized.

Think of it like this. What are the two primary images God uses in the Bible to describe His relationship to his people? Yes, He uses religious imagery like congregations and political imagery like kingdoms, but most often it’s the imagery of marriage and children. Part of being married and having kids is glorious. The way you can be in a crowd of people yet know that there is that one special someone who is yours and whose you are. The simple joy in seeing letters come in for Mr. and Mrs. So-and so. The way your child’s eyes light up as you swing her around. That is a joy that puts any night out at a bar to shame.

Yet not all of marriage and child-rearing is so glamorous. There’s the time your wife is sick, and you are stuck handling your own household duties and hers. There are the times when your child is producing things from his body which make you want to vomit yourself. This is how God describes His love for His people, and this is the love He calls us to have for others.

This is God’s love, the love of a husband for his bride in sickness and health, the love of a mother for her child, in all its precious incompetence. This is the love of the Good Samaritan. This is the love we are to have for our neighbors. When faced with the difficulty of loving our neighbor, whether that neighbor is the enemy at the gates or the family member in your home, let the love which God has had for you spill out from you onto this undeserving person. As we have been loved by God, let us love our neighbors for God .

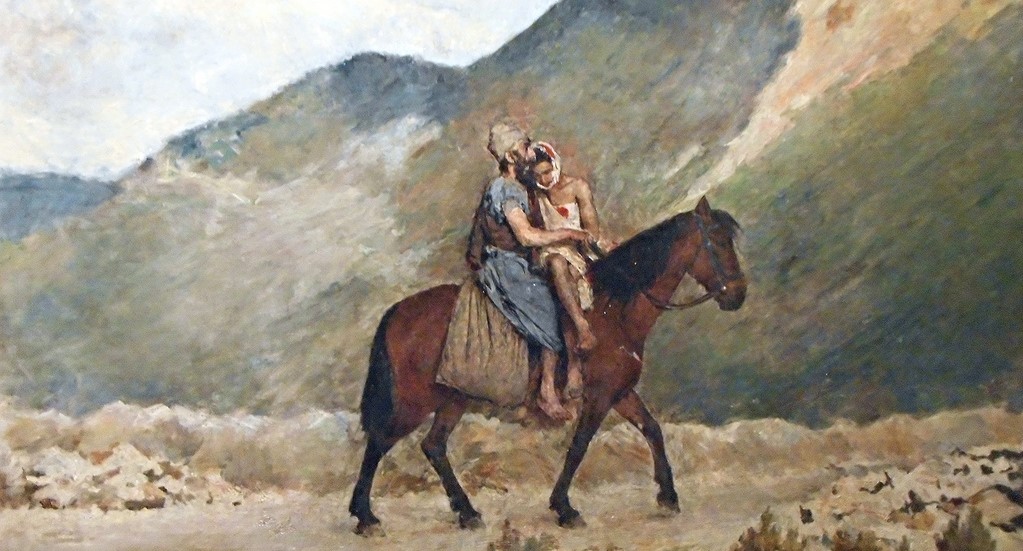

Image: Google Images, “The good Samaritan” by Alfonso Cattaneo