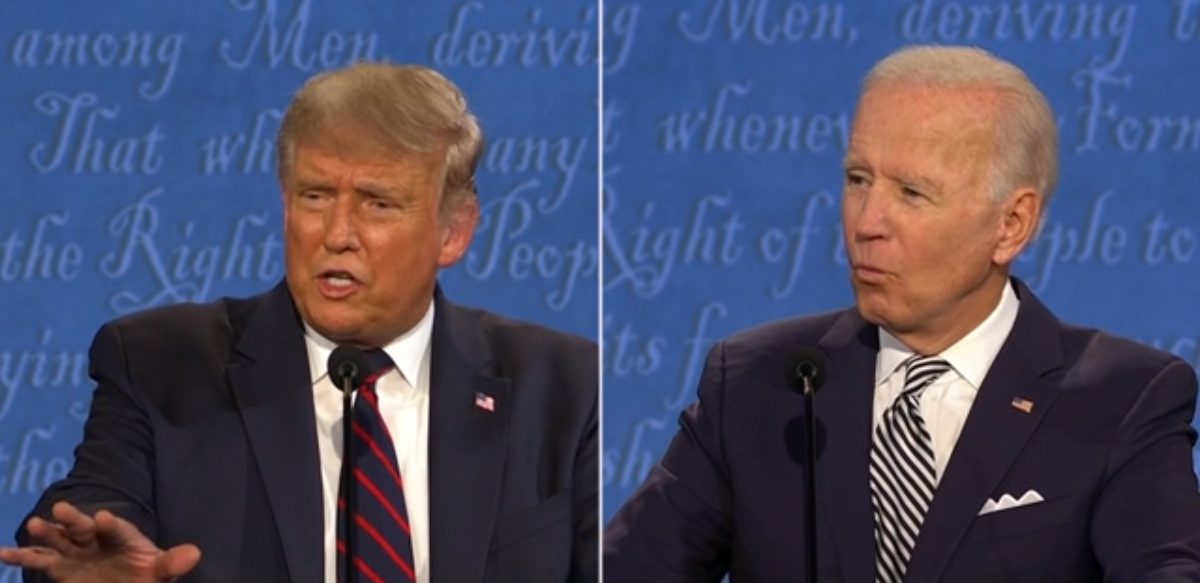

There are no highlights from Tuesday night’s presidential debate. There are, however, plenty of “lowlights”: name-calling, untruths, anger, vitriol, interruption. It was a debacle on every level.

During the debate, my friend Trevin Wax tweeted, “Neil. Postman. He saw this coming forty years ago,” referring to how the author of Amusing Ourselves to Death, who described what happens in societies when societies’ entertainment replaces truth and celebrity-ism replaces virtue.

In addition to Postman, a speech called “A World Split Apart,” given at the Harvard University commencement on June 8, 1978, by Russian dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn has proven to be the best decoder of our cultural moment. Today, we live downstream from, in the wake of, what Solzhenitsyn attempted to describe to his booing audience.

For example, Solzhenitsyn described how the West had replaced the pursuit of happiness by virtue with a pursuit of happiness by stuff:

“Every citizen has been granted the desired freedom and material goods in such quantity and of such quality as to guarantee in theory the achievement of happiness … however, one psychological detail has been overlooked: the constant desire to have still more things and a still better life and the struggle to obtain them imprint many Western faces with worry and even depression … The majority of people have been granted well-being to an extent their fathers and grandfathers could not even dream about; it has become possible to raise young people according to these ideals, leading them to physical splendor, happiness, possession of material goods, money and leisure, to an almost unlimited freedom of enjoyment. So who should now renounce all this, why and for what should one risk one’s precious life in defense of common values?”

When the pursuit of virtue is undone by materialism, words are redefined. Specifically, Solzhenitsyn suggested, freedom:

“Destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society appears to have little defense against the … misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people, such as motion pictures full of pornography, crime, and horror. It is considered to be part of freedom and theoretically counter-balanced by the young people’s right not to look or not to accept … Such a tilt of freedom in the direction of evil … [was] born primarily out of a humanistic and benevolent concept according to which there is no evil inherent to human nature; the world belongs to mankind and all the defects of life are caused by wrong social systems which must be corrected.”

Solzhenitsyn then specifically points a finger at the press:

“The press too, of course, enjoys the widest freedom. But what sort of use does it make of this freedom? … How many hasty, immature, superficial and misleading judgments are expressed every day, confusing readers, without any verification. The press can both simulate public opinion and miseducate it. Thus, we may see terrorists described as heroes, or secret matters pertaining to one’s nation’s defense publicly revealed, or we may witness shameless intrusion on the privacy of well-known people under the slogan: ‘Everyone is entitled to know everything.’ But this is a false slogan, characteristic of a false era. People also have the right not to know, and it is a much more valuable [right]. The right not to have their divine souls stuffed with gossip, nonsense, vain talk. A person who works and leads a meaningful life does not need this excessive burdening flow of information. … In spite of the abundance of information, or maybe because of it, the West has difficulties in understanding reality such as it is.”

At the root of all of this, Solzhenitsyn suggested, is what he called “spiritual exhaustion”:

“The human soul longs for things higher, warmer, and purer than those offered by today’s mass living habits, introduced by the revolting invasion of publicity, by TV stupor, and by intolerable music … There are meaningful warnings that history gives a threatened or perishing society. Such are, for instance, the decadence of art, or a lack of great statesmen. There are open and evident warnings, too. The center of your democracy and of your culture is left without electric power for a few hours only, and all of a sudden, crowds of American citizens start looting and creating havoc. The smooth surface film must be very thin, and the social system quite unstable and unhealthy.

There is only one solution with which Solzhenitsyn left his audience:

“Even if we are spared destruction by war, our lives will have to change if we want to save life from self-destruction … If the world has not come to its end, it has approached a major turn in history, equal in importance to the turn from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. It will exact from us a spiritual upsurge: We shall have to rise to a new height of vision, to a new level of life where our physical nature will not be cursed as in the Middle Ages, but, even more importantly, our spiritual being will not be trampled upon as in the Modern era.”

And then he concludes:

“No one on earth has any other way left but — upward.”

God help us.

Topics

Christian Living

Christian Worldview

Culture/Institutions

Elections

Politics & Government

Worldview

Resources:

First 2020 Presidential Debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden

C-SPAN | YouTube | September 29, 2020

Alexander Solzhenitsyn | American Rhetoric | June 8, 1978

Neil Postman | Amazon

Have a Follow-up Question?

Up

Next