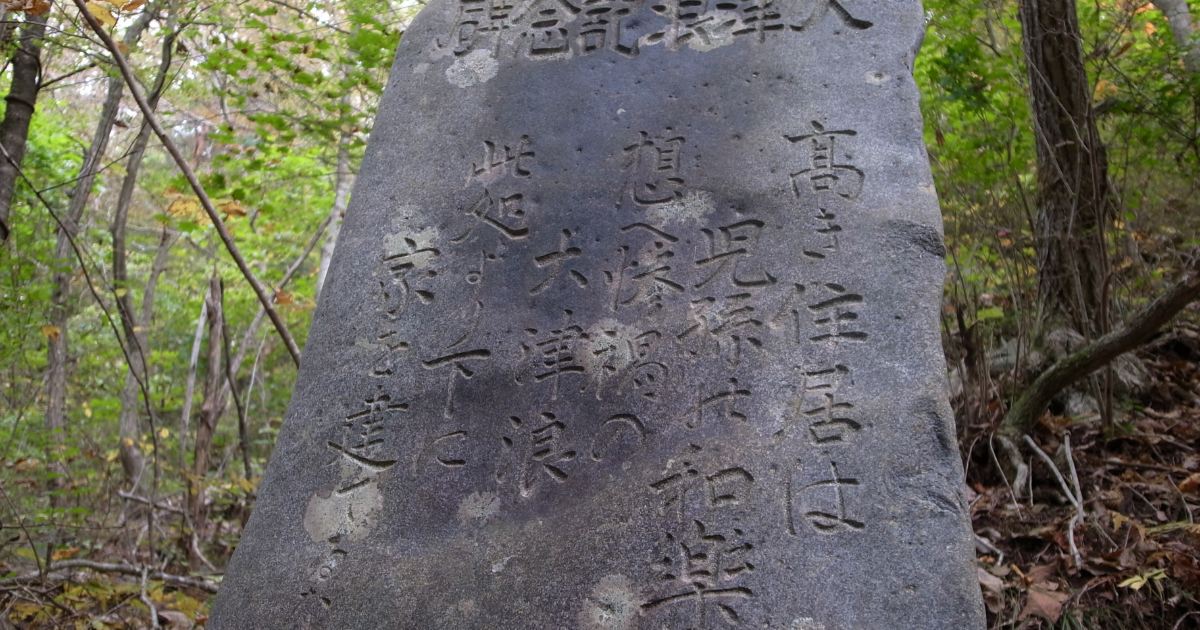

“Remember the calamity of the Great Tsunamis. Do not build any homes below this point.” Those are the words inscribed on what are appropriately called “Tsunami stones,” markers left by previous generations in Japan that warn future generations of difficult lessons learned.

After decades with no tsunamis, especially given new technologies such as better seawalls and flood-proof construction, these kinds of warnings were increasingly seen more as relics than wisdom from past experience. They became easier to ignore and, as a result, in 2011, many perished.

The villagers of Aneyoshi, however, heeded the instructions their forebears placed on a tsunami stone in the 1930s, and they moved their village to higher ground. They not only survived the 2011 tsunami, but the one in 1960 as well.

When I learned about these stones recently from a friend, I immediately thought of a parable by G. K. Chesterton about those committed always to reform:

“… let us say, for the sake of simplicity, (there’s) a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

In other words, we should never remove a fence until we know why it was put up in the first place.

There’s no doubt we live in a culture that’s quite committed to clearing away all kinds of moral fences in all areas of culture, often replacing them with new fences in new places. What used to be unthinkable is now unquestionable. What used to be unquestionable is now thought of as quaint, puritanical, and in some cases, oppressive and evil. What used to belong to families now belongs to the state. The guilty are now victims; the good guys now the bad guys; the essential now non-essential.

Even in the Church today, perhaps especially in the Church, there’s a great temptation to move fences, to lower or remove moral standards in a well-intentioned, but often misguided, attempt to be “welcoming.” Almost always, these moves are made in the name of “love,” as if the key missional strategy of the Church is to remove any and all barriers to the Gospel, including any that are inherent and essential to the Gospel itself.

Often the tsunami stones of moral truth, which the Church has embraced and taught faithfully for 2,000 years, are seen as obstacles to progress. The first and greatest commandment to “love God,” at least as we’ve long understood it, seems to be in conflict with the second one of “loving neighbor.” Truth and love are increasingly seen as incompatible in the fog of secularism and moral relativism. Believing the truth about human sexuality, which went unquestioned in Christian history until yesterday, is considered unloving. Speaking that truth? Well, that’s downright cruel.

This, of course, gets it exactly backwards. What’s cruel, if moral realities do exist and if we live in a world designed and not accidental, is to remove fences and ignore stones. It’s cruel to tell someone who’s not okay that they are. It is not only possible to be loving and to tell the truth, it is in fact, impossible to be loving without the truth.

Learning to hold truth and love together, especially in a culture committed to their divorce, is now a key task of the Church.

In a wonderful scene near the beginning of C. S. Lewis’s “The Silver Chair,” Aslan is preparing a young Jill Pole for a rescue mission in Narnia. His instructions are clear, but his instructions about his instructions, even more clear:

“…first, remember, remember, remember the signs. Say them to yourself when you wake in the morning and when you lie down at night, and when you wake in the middle of the night. . . And secondly, I give you a warning. Here on the mountain I have spoken to you clearly: I will not often do so down in Narnia. Here on the mountain, the air is clear and your mind is clear; as you drop down into Narnia, the air will thicken. Take great care that it does not confuse your mind… Remember the signs and believe the signs. Nothing else matters.”

If this reminds you of God’s instructions to Israel in Deuteronomy, it should. Most of the Bible is about remembering. There is no way to live out what God has taught us and called us to, no way to love God or neighbor, without remembering.

At the most foundational level, each of the five modules of the Colson Center’s upcoming virtual event this month, “Truth. Love. Together.” is all about remembering. In our culture, there is no remembering without defining. The first module, featuring Os Guinness, Sean McDowell, Abdu Murray, and Natasha Crain is about defining, or remembering, what truth is. The second module, with Joni Eareckson Tada, Pastor Chris Brooks, Louis Markos, and me is about defining, or remembering, what love is.

From remembering, we move into doing. In module three, Andy Crouch, Brett Kunkle, Lauren and Michael McAfee, and Max McLean will challenge us on how we can “Become People of Truth and Love.” In module four, the great apologist Lee Strobel, Promod Haque, Uju Ekeocha, and J. Warner Wallace will remind us “Why Telling the Truth Is an Act of Love” and how we can indeed do that–tell the truth in love. Finally, Katy Faust, J. P. DeGance, and this year’s Wilberforce Award Winner, Bob Fu, will teach us how to “Love the Victims of Lies” by speaking the truth.

This is a 360 degree experience on “Truth. Love. Together.” And, it is absolutely free. Just come to WilberforceWeekend.org to register. All five modules, with more than 20 sessions, will be available live or on demand. Again, the cost is free.

Photo via Wiki Commons

Topics

Resources:

Have a Follow-up Question?

Up

Next

Related Content

© Copyright 2020, All Rights Reserved.