“For in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God, through faith. For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to promise.” – Galatians 3:26-30

The answer to the first question is easy.

No. Jesus wasn’t white.

If only the rest of this situation were so simple.

At one point in a trip to Pine Ridge Indian Reservation back in 1998, I made a play for cool points. Wanting to impress both my fellow Anglos as well as those Lakota we’d come to serve, I asked a local Christian how we could best present the gospel to one of “his” people. Instead of the pat on the back for my sensitivity I’d been expecting, I was laughed at. It wasn’t a mean laugh, but there was a chuckle and an unstated “silly Wasi’chu” in his eyes. He simply said, “The same way you would for anybody else!”

That moment has stuck with me all these years. I’d never have put it this way, but I’d been acting as though our different races required different Christs. Certainly, someone’s ethnicity plays a role in the way we present the gospel, just as their socio-economic status, personality type, gender, and a host of other factors have their place. But when we think of our relationship to Jesus, and to one another, as one built primarily on our own idiosyncratic genetic or cultural characteristics, we cut ourselves off from the union in Christ which grants us our salvation and we separate ourselves from our shared status as image bearers of God which grants us the basis for ethics and viewing one another with uniform dignity.

But when we think of our relationship to Jesus, and to one another, as one built primarily on our own idiosyncratic genetic or cultural characteristics, we cut ourselves off from the union in Christ which grants us our salvation and we separate ourselves from our shared status as image bearers of God which grants us the basis for ethics and viewing one another with uniform dignity.

Every few years this controversy over Christ’s ethnicity gets stirred up again. In 2012 it was then-FOX News anchor Megyn Kelley saying that Jesus was white, and a few months ago the BBC jumped into the fray with an African Jesus. Now, Kelley later walked her comments back, and our UK friends were making another point, but the confusion still remains.

This is more than a topic for media elites to dabble in. Once I heard a white supremacist say that Jesus had to have been white and certainly couldn’t have been Jewish since the Jews wanted him dead. Another time I had a student become quite offended when I told the class that Jesus was not African, and, during that same trip to Pine Ridge, two Lakota boys looked at me in shock after I corrected their coloring by saying that Jesus wasn’t white and probably looked more like them than like me.

It is not only Jesus’ ethnic background where this sort of thing has come up. One of the most curious ways is the role played by the Lost Tribes of Israel in similar racial mythologies. As the Bible states in the books of II Kings and II Chronicles, the people of the northern kingdom of Israel were exiled from their home around the year 724 BC as a part of Assyrian imperial policy. Aside from the few brought back as priests for their successors, no one has heard from them in nearly 3000 years. In the time since people have tried to find these lost tribes, usually to the benefit of their own ethnic group. There have been the claims that the tribes are the European nations, the Anglo-Saxons, the Native Americans, the United States, non-whites in the Americas, and so on.

There’s no real basis for any of these ideas, but it’s also telling. There is in a great many of us a longing for a connection to the divine, for an ability to say that these people are the in-group, the good people, and that those people are the out-group, the bad people. Sometimes we do it, as here, with race. “God loves us more because of our race.” Other times it’s our income level, political party, nationality, sexual orientation, or other subculture.

The ethnicity of Christ can seem of great importance in this way. By connecting in some way to Him through our own race, we feel that we have a part of Him that we would lack were we unconnected. To have Him be one of ours means that He is, in fact, ours. This establishes our hope in our identity, not His.

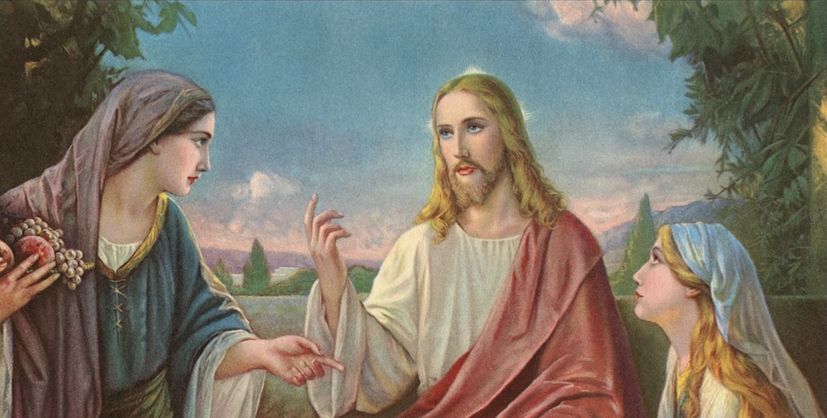

So, what was the truth? No, Jesus wasn’t white. He was a Middle Easterner, and, after a fashion remains so to this day. There are no descriptions in the Bible as to what He looked like, and ancient portrayals are either idealized, made by anti-Christian “artists,” painted centuries later, or all three at once. There are, however, a few inferences we can make, both from the Scriptures and a general knowledge of history.

From the prophecies of Isaiah, written some 700 years before Christ, we can surmise that there was nothing extraordinary in His appearance, nothing to make Him stand out from the general population of the eastern Mediterranean world. For comparison take the mummy portraits made during the long centuries of Roman domination of Egypt, or images from a Synagogue in Syria. Dark hair, dark eyes, “olive” skin, and, by our standards, rather short.

Perhaps if we want to know what Jesus looked like, it would do us well to look to the people who live in the same part of the world today as He did. Saudi Arabians, Jordanians, Palestinian Arabs, Lebanese, Egyptians, Syrians, Assyrians, and so on. As with any large region of the world, particularly one at the crossroads of cultures as this one, there is a delightful variety of appearances within the Middle East, with some people looking European and others looking African. Jesus’ own kinsmen, the Jews are among the most diverse looking people in the world, having been scattered by the Romans before beginning to return to the Middle East after the Holocaust. However, we can get a general idea from neighboring and related peoples.

He wasn’t European or African, He wasn’t Latino or Native American, He wasn’t South or East Asian. and He wasn’t Aboriginal Australian or Pacific Islander. He was a Jew, and a Middle Eastern Jew at that. That’s exactly the person God had always intended Him to be, even if it’s not who we wanted Him to be, even if He isn’t a member of our little group.

If we see the problem in life as smaller than all of humanity, if we reduce it to that race, culture, nation, and see “them” alone as the cause of our misfortunes, we deny the promise of God in the Garden. When we presume that the solution to life’s problems is something less than the work of Christ and think that “this” will save us, we create a god in our own image and deny the promise of God to Abraham and David.

When we hyphenate our faith, when we approach our identity in Christ as a subset of our own cultural identity, rather than the other way around, we do more than express ourselves in our own unique way. What we do then is to undermine the reality and implications of the Christian Worldview.

If we see the problem in life as smaller than all of humanity, if we reduce it to that race, culture, nation, and see “them” alone as the cause of our misfortunes, we deny the promise of God in the Garden. When we presume that the solution to life’s problems is something less than the work of Christ and think that “this” will save us, we create a god in our own image and deny the promise of God to Abraham and David.

You see, Jesus had to be a member of two races. I don’t mean that He was multiethnic, although with the likes of Rahab and Ruth in His bloodline that’s true, too. I mean that He had to be a member of the human race and a member of the Jewish race.

The first requires that we abandon all pretensions about our own little ethnic group. We are not better or more special or somehow closer to God on the basis of our specific ancestry. The promise of a coming Redeemer given in Genesis 3 was given to the entire human race encapsulated at that moment by Adam and Eve. It was not given to one group of their heirs over against another but to all their many and manifold descendants as one single human race.

The second similarly demands that we give up the expectation that it’s something in us which draws God along His plan of redemption. God in Christ came to Earth as a Jew because that’s what He promised to Abraham and to David. God’s scheme of salvation was not a free-for-all religious action where our efforts towards the divine justify us in His eyes. No, it was accomplished and applied through His plan, brought about by His chosen line, and enacted by His Son, Jesus Christ, the construction worker from a hick town in an unkempt corner of a mighty but long dead empire.

So, let’s set aside our attempts to connect with God via our identity and instead identify ourselves by this short, swarthy Jewish man from centuries past. That’s God’s plan. I think it’s best with stick with it.

In Jesus’ name, Amen.

Timothy D. Padgett, PhD, is the Managing Editor of BreakPoint and the author of Swords and Plowshares: American Evangelicals on War, 1937-1973 as well as editor of the forthcoming Dual Citizens: American Evangelicals and Politics.

Image: YouTube