George Washington Carver was born a slave in Missouri around 1864. His parents had been bought in 1855 by Miles Carver, a German immigrant. When George was a week old, he was captured along with his mother and sister by Confederate raiders from Arkansas, who sold them as slaves in Kentucky. Miles tracked George down and got him back, though not his mother or sister. The Carvers decided to raise George as their own son, and “Aunt Susan” taught him to read. He was too sickly to work in the fields, so he began studying plants, developing natural pesticides and fungicides, and finding ways to improve the soil. He was so successful that local farmers began to call him “the plant doctor.”

Conversion

George came to faith in Christ as a young boy. He described the event in a letter he wrote in 1931:

I was just a mere boy when converted, hardly ten years old. There isn’t much of a story to it. God just came into my heart one afternoon while I was alone in the ‘loft’ of our big barn while I was shelling corn to carry to the mill to be ground into meal.

A dear little white boy, one of our neighbors, about my age came by one Saturday morning, and in talking and playing he told me he was going to Sunday school tomorrow morning. I was eager to know what a Sunday school was. He said they sang hymns and prayed. I asked him what prayer was and what they said. I do not remember what he said; only remember that as soon as he left I climbed up into the ‘loft,’ knelt down by the barrel of corn and prayed as best I could. I do not remember what I said. I only recall that I felt so good that I prayed several times before I quit.

My brother and myself were the only colored children in that neighborhood and of course, we could not go to church or Sunday school, or school of any kind.

That was my simple conversion, and I have tried to keep the faith.

Education

Because blacks were not allowed in the schools in his hometown, George walked ten miles to a town where there was a school for blacks. He arrived after the school had closed, so he spent the night in a barn. The next day he met a woman named Mariah Watkins from whom he hoped to rent a room. She asked his name, and he said, “Carver’s George,” as he had always been called. She told him that his name was now George Carver, and that he needed to learn all he could and then come back and share his knowledge with the people. That left a powerful impression on him for the rest of his life.

After attending several other schools, he eventually got his high school diploma. Although he was accepted at Highland College, when they found out he was black, they refused to admit him. Instead, he began farming land he received for homesteading. In 1888 he got a loan to pay for education, so he went to Simpson College in Iowa to study art and piano. His skill at drawing flowers and plants led his professors to encourage him to apply to Iowa Agricultural College (now Iowa State). He was accepted and became the school’s first black student. Carver was so successful that his professors talked him into staying for a master’s degree and becoming the college’s first black faculty member. He completed his degree in 1896. By this point, he had developed a national reputation as a botanist.

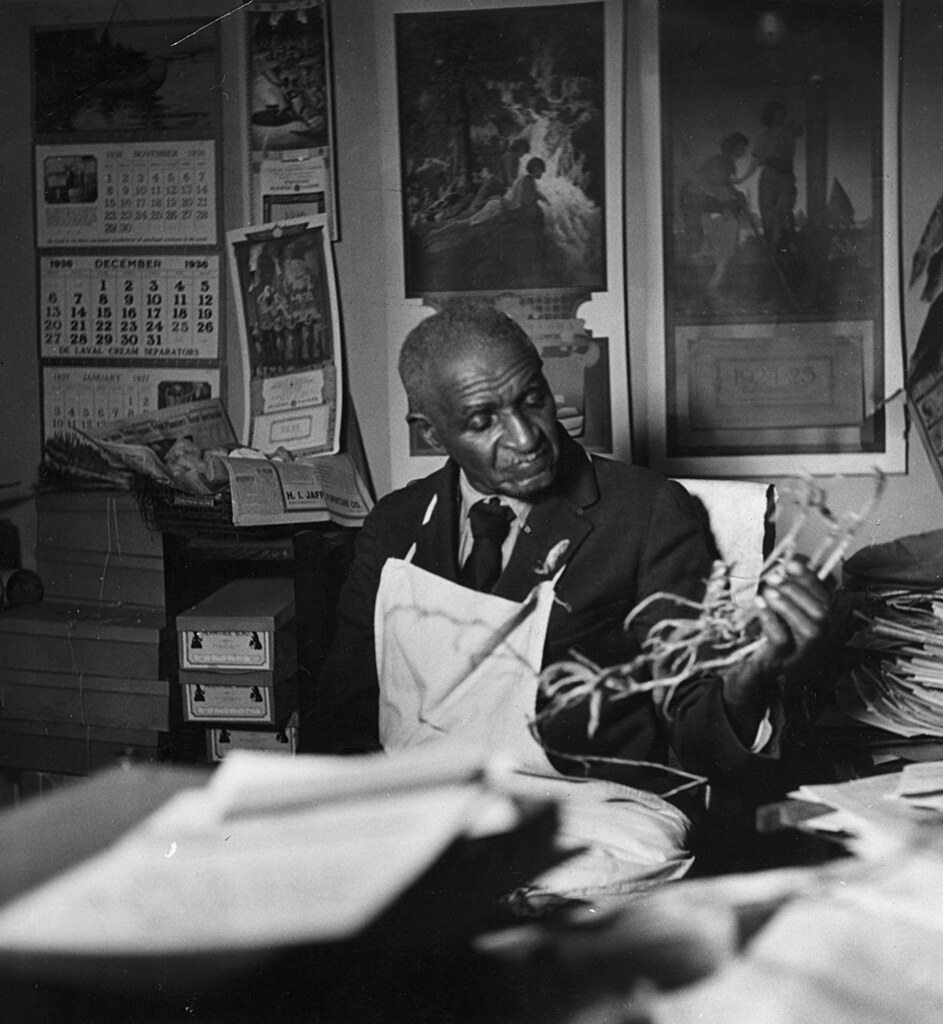

Career

In 1896, Booker T. Washington recruited Carver to head the Agricultural Department at Tuskegee Institute (not Tuskegee University), a position which he held for 47 years. In that position, he was as concerned about character development as he was in academics; he even began teaching a Bible Study at the request of his students.

His agricultural research at Tuskegee led to a system of crop rotation to repair soils depleted by cotton cultivation. He discovered that alternating cotton with sweet potatoes or legumes such as peanuts not only increased the yield of cotton but also produced food and diversified the cash crops for the farmers. Carver then began developing alternate uses for sweet potatoes and peanuts to increase the market for the new crops. He ultimately found 118 derivatives from sweet potatoes and 300 from peanuts. Later, when the boll weevil devastated cotton crops, Carver’s work on alternative crops saved Southern agriculture.

All this brought him to the attention of important figures in government, including Theodore Roosevelt. He also became one of the very few Americans admitted to the Royal Society for the Arts in England (1916). In 1921, he testified as an expert witness to the House Ways and Means Committee on the importance of peanuts to the American farmer in response to the threat to the industry from cheap imports from China. Although the Southern representatives were initially shocked that a black man was testifying before Congress, the committee kept extending his time in view of his obvious expertise and intelligence. His testimony influenced legislation on imports and made him a celebrity in America.

Carver used his fame to educate American farmers on best practices and to promote racial unity. All through his career he had sought out Christians for fellowship. He saw in the Gospel the means to overcome racial and social divisions. Three American presidents consulted with him during this period, and he continued his agricultural research.

In January 1943 Carver fell down a flight of stairs at the Tuskegee Institute. He died of complications from the fall a few days later. His epitaph reads, “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”