With 10,000 years of human history in the books, there is rarely a day that can go by that is not the anniversary of one thing or another. But this week brings us something different. This week is the anniversary of a day which clearly changed history forever. Or two days, rather.

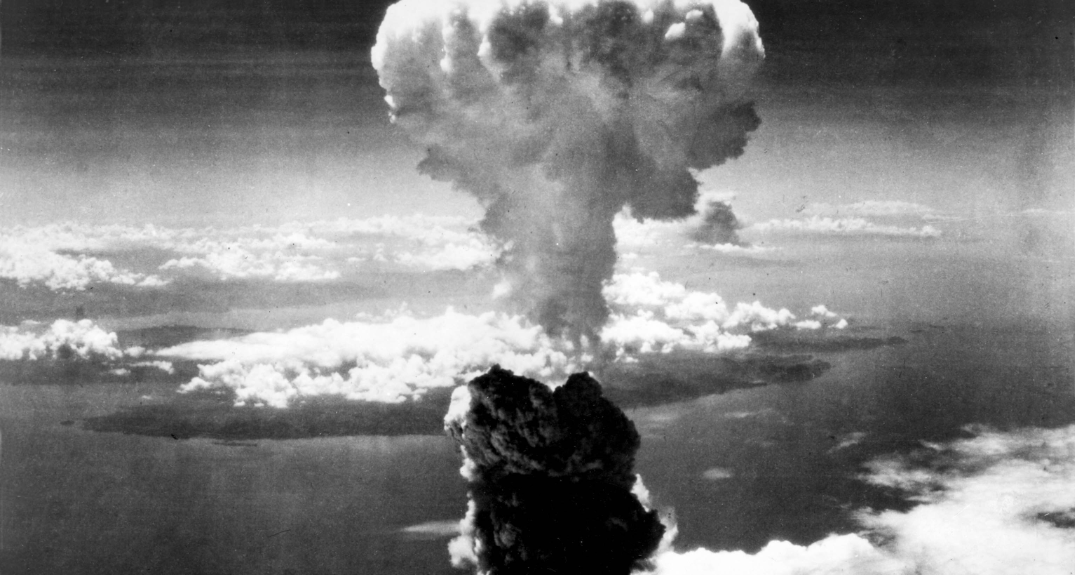

In the early morning of August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic weapon ever used in combat. Three days later, it dropped a second bomb. Thankfully, the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki constitute the only times that such devices have been used against human beings.

While the deaths involved in these air raids made up only a tiny portion of all those killed in that gargantuan war, it was very clear to everyone around that the game had changed. Before this time, to create a similar level of destruction, it would have taken hundreds of planes and thousands of airmen. Now a single bomber with a crew as few as ten could eliminate a city and kill tens if not hundreds of thousands of people in an instant. And this does not even include the lingering death due to radiation sickness.

The world had not yet reached the point of tens of thousands of nuclear weapons topping thousands of intercontinental ballistic missiles, as it would see in the 1970s and 1980s, but, even then, people recognized the significance of what had occurred. Human ingenuity had finally reached the point where it could destroy human civilization.

To say that this was, and is, a controversial move by President Truman would be to put it mildly. Some have gone so far as to connect these attacks with the worst of Auschwitz and the Nazi concentration camps. Even those who supported the Allied war effort had some qualms about how this particular operation was conducted. One man, writing in a Christian magazine in October of that fateful year, had this to say:

In an orgy of blood and human misery one terrible weapon of destruction after another was turned upon flesh and blood. The world’s best in mind and matter was flung with abandon into the struggle. And when we had reached the point where many were imagining that nothing further in the way of bigness or badness could surprise them the curtain was raised on the horror of Hiroshima.

Similarly, just days after the attacks, an American pastor preached a sermon, saying, “The world will never be the same from that hour when the first atomic bomb to be used in war was dropped on Hiroshima. We can never go back to that former age. What the future holds, no one knows.” He would go on to state that this moment in Japan had caused more of a fundamental shift to the human condition than all the ups and downs of the Renaissance and Reformation put together.

Even with the awareness that this was one Pandora's Box that could never be closed again, observers in America and around the world did not wholeheartedly reject the existence of atomic warfare or even its use in this instance.

This was no simple historical curiosity for those in that time, but it affected us all. On his Pasadena radio show in 1952, Carl F. H. Henry argued that there were questions of guilt to be considered, and this not only for the political and military leadership of the nation. He said:

They dropped the bomb, and if there was any guilt in the dropping of that bomb, in the sudden erasure of those Japanese lives, in the distorted features and ugly scars and suffering bodies which we bequeathed to a multitude of blistered survivors, we share in that guilt.

Even with the awareness that this was one Pandora’s Box that could never be closed again, observers in America and around the world did not wholeheartedly reject the existence of atomic warfare or even its use in this instance.

Instead, many moralists, ethicists, and theologians alike came to the conclusion that nuclear weapons were a necessary, if not evil, at least darkness that had to be endured. Putting aside until another day the question of later Cold War strategies involving thermonuclear bombs, there are some issues regarding this first use of atomic weaponry which can, in turn, point us to other questions about the finite nature of human moral perception.

There are a great many suggested objections to the use of atomic weapons in 1945 – the sheer destruction and immense casualties, a supposedly racist motivation by the U.S., the significance of the August 8 Soviet invasion of Manchuria, the utter impotence of the Japanese military that late in the war, and so on. Unfortunately, there’s insufficient space here for a thorough discussion, so we’ll have to leave it at saying each of these fails in one way or another as an adequate objection.

Instead, I’d like to focus here on a single objection, not because it’s the easiest to dismiss but because it’s the hardest to answer. The strongest objection to the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 is that they did not meet the criteria of Just War, specifically that aspect known formally as jus in bello. In order for a war, or even part of a war, to be considered just, it must not only be done for the right reasons, but it must be done in the right way. That is to say, just because something works in war, it doesn’t follow that it’s moral to do it.

In this case, the concern is that while using atomic bombs against military or industrial sites could be morally acceptable, using them against Hiroshima and Nagasaki was immoral because these were not legitimate targets. So, using the bomb against the Japanese Fleet is one thing, but hitting cities like these was not kosher.

This may seem strange, given the intensity of the Allied air campaigns against Japanese and German cities. However, those who defend those campaigns argue that these other places were legitimate targets since they were homes of much of the Axis military infrastructure which enabled them to continue the war. The same argument cannot be applied quite so easily to the two sites of atomic attack.

One of the reasons that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were selected as targets is that, as they had had no significant industrial capacity, they had not yet been bombed to a significant degree. This meant that they were largely still standing, and this was just what the U.S. was looking for. They wanted it clear that they had something so awful that it scared Japanese leadership into ending the war, something they’d been unwilling to do up to this point.

This clear demonstration of the bombs’ great power would have been far less effective in another city like Yokohama or Tokyo which had already been significantly leveled by previous fire-bombing campaigns. Without a gruesome before-and-after image, the Japanese authorities may well have not realized just how devastating the bombs were. But this brings us awfully close to a matter of killing 200,000 people, not because doing so would have materially kept the enemy from continuing the fight, but to make a diplomatic point.

We want to believe that if we study carefully enough, research thoroughly enough, or love hard enough we'll come up with a solution for every complication we face. But, it's not always that way, is it? Our vaunted intelligence and keen sympathies, which we deem sufficient to judge all things, cannot peer through the misty moral darkness of our post-Fall world. We need a surer light, a guide that comes from a source not bound by our limitations.

So, what are we left with, morally speaking? Something between a “maybe” and a “probably.”

Given the situation at hand, it was probably the right thing to do to drop the bombs on Japan. Had the Americans gone ahead with the planned “Downfall” invasions of Kyushu & Honshu, the death toll would have made Hiroshima and Nagasaki seem pale in comparison. Some estimates of American casualties alone ranged into the hundreds of thousands. Given that fully 1/4 of the civilian population of Okinawa was killed in the battle for that island, we are talking about millions upon millions of civilians dead in Japan proper.

Doing nothing wasn’t a moral option. The Japanese empire had, for years, been perpetuating a great evil upon its neighbors. Were it not for the intervention of the United States and its allies, there is little doubt they would have continued doing so as long as they could. In fact, they were so intent on committing these atrocities that it took the utter devastation of their homeland to get them to desist.

We are left with a moral quandary. Anything we did left us with no easy answer. We stopped a great evil and saved countless lives, but what did we have to do to do it? This is a concern for any time we think to take up the sword, but it’s also true for a great many other moral crises we may face.

Maybe for you the questions of August 1945 are straightforward, one way or the other. But, I’d bet that there is some thing in your life or perhaps from history where you don’t know what the right answer is. Or rather, you don’t know which partially wrong answer is best. What was right back then? What is right right now? We don’t know, and, what’s more, we may never know.

This is a scary place to be.

It is here that we come to the end of ourselves. And not only ourselves alone, but the end of what our collective human nature can do for us. We would dearly love it if it were the case that we could always see the moral path in a forest of immoral possibilities. But that is not our lot.

We want to believe that if we study carefully enough, research thoroughly enough, or love hard enough we’ll come up with a solution for every complication we face. But, it’s not always that way, is it? Our vaunted intelligence and keen sympathies, which we deem sufficient to judge all things, cannot peer through the misty moral darkness of our post-Fall world. We need a surer light, a guide that comes from a source not bound by our limitations.

Now we Christians may think to ourselves, “Yes, yes. Those non-believers need to appeal to the Bible.” That’s true, but it’s not only for them. Even believers can live as de facto atheists when they fail to accept that they need from God’s Word more guidance than their own perceptions and opinions can provide. If our only appeal to God’ revelation comes when it is comfortable for us or otherwise amenable to our self-satisfied understanding, then it is not God that we follow but only our own projected prejudices.

Between Eden’s Fall and the arrival of the New Jerusalem, every single decision that we make will be hampered by our ordinary human frailty and our extraordinary sinful nature. This world will bring us troubles that are too big for us to handle. Whether we’re talking about grand issues of war and peace or more mundane questions of finding peace in our daily lives, our only hope is to rely on the One who is Himself the light.

We have a choice to make: Will we go on in the pretense that we can know the truth of all things, or will we accept our discomfort, admit our frailty, and look for something better than what we can provide for ourselves?

Timothy D. Padgett, PhD, is the Managing Editor of BreakPoint and the author of Swords and Plowshares: American Evangelicals on War, 1937-1973

Image: Mushroom cloud over Nagasaki, August 9, 1945, Google Images