Judge not, that you be not judged. For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged, and with the measure you use it will be measured to you. – Matthew 7:1-2

“Judge Not!” How many times have we heard this in the midst of a cultural debate? And why shouldn’t we? Quoting Jesus here is the ultimate trump card for Christians going “squishy” on sin, and it’s the one verse that non-Christians hold as infallible.

It makes for a nice catchphrase, suitable for a bumper-sticker, t-shirt, or social media post, but, by itself, it makes for a really lousy way to live out the Christian Worldview. As a stand-alone principle, it’s inconsistent with our common sense understanding of the world and, more importantly, it’s out of alignment with the practice and principles of God’s word.

Nearly every time we publish something critiquing certain kinds of sin, we get pushback from readers saying that we shouldn’t judge others. Whether we’ve been talking about media choices, pastimes, or sexual issues, the language is pretty much the same. “Since God is a God of compassion, love, and forgiveness, Christians shouldn’t go around condemning people for their sins. It’s not our job to judge others but only to love them.”

So the argument goes, anyway.

One of my first reactions to these kinds of comments is to reply, “Pot, meet Kettle.” After all, it takes a special kind of logic for someone to say that it’s wrong to tell others they’re wrong. Is it unchristian to tell others that they’re wrong, or isn’t it? The entire basis of this line of reasoning is self-contradictory since, if it’s out of accord with the will and word of God to be judgy, how then can we be judgy by telling others not to be judgy?

I think what people often really mean when they judge others for judging is that it’s not Christian to judge others for certain, specific sins. Okay, so I don’t like it when others put words in people’s mouths and declare what they “really mean,” yet here I go doing it myself. Nonetheless, I think it’s fair to say that there’s a gap between this call to emphasize the forgiveness of God and the willingness of nearly all of us to find some sins worth calling out.

As I’ve written elsewhere, we all have our favorite sins that we think are particularly bad and which deserve, therefore, particular condemnation. Other sins, on the other hand, slip around the edges of our moral compass and don’t seem worth much of a fuss.

For some of us it is social sins like racism and economic exploitation that stick in our craw, while, for others, it is more individual failings like sexual impropriety or hurtful words which draw our condemnation. Others still may have an entirely different schematic of scandalous sins in mind. Whatever the case, and however much we might protest to the contrary, there is for all of us some sin that we feel deserves clear and public condemnation.

While that smacks of hypocrisy, a better critique of judging is the suggestion that we shouldn’t do this very thing, that we shouldn’t rate one sin as being better or worse than others. We shouldn’t judge others because we have our own sins. In one sense, this is absolutely right. Your sinfulness isn’t worse than mine, nor mine than yours, but, with good reason, none of us actually lives like this is a universal principle denying the ability to discern the better from the worse.

Look. Sin is sin. That’s true. And however we rate the relative harmfulness of given sins, all sin leaves us condemned. The sweetest, kindest, gentlest, old lady Sunday School teacher you ever met is as much in danger of the fires of Hell without Christ as the vilest, murderous, pedophile imaginable. As troubling as it is to our hearts and pride, we are not saved by our goodness nor blocked from salvation by our badness. Even the best of us on our own merits does not deserve the grace of God, and even the worst of us is not beyond His mercy because of the work of Jesus.

However, while all sins are equally sin, not all sins are equal in effect. A driver going one mile over the speed limit and another going 50 over are equally breaking the law, but the one is clearly crossing the line more than the other. If you think I’m being petty, consider this. What if this speeding was in a school zone? Would that change your perspective?

We all consider harming a child to be among the worst of all sins, but none of us treats all such harm as equal. Do we treat a father who yells at his child the same as if he beat her? Or molested her? Those who would react to each of these the same are few and far between. What is more, they’d be wrong if they did treat them the same.

While it is wrong to judge one sin more harshly than another simply on the basis of our personal preference, it is entirely appropriate to make more of a fuss of those sins we recognize make more of a mess of this world. How can we not become more enraged at the malignant corruptions around us that enslave and fracture the lives of all they touch? How can we not consider the aftereffects of our moral failings upon God’s creation and, most importantly, on those of His Image Bearers who live around us? Refusing to judge certain grievous sins more harshly than others is not gracious but an act of gross immorality and displays a distinct lack of love.

This isn’t a call to a libertarian view of sin, one which relegates tough choices to a utilitarian calculus of harmful vs. helpful. While we may appeal to the reality of common grace, natural law, and general revelation to get us partly on our way, limiting ourselves to our own perceptions will leave us perpetually under the sway of whatever group has the most power at a given time. If we’re to avoid the pitfalls of situational ethics and might-makes-right morality, we’ll need something more substantial than human frailty to discern right from wrong.

Anyone who’s familiar with BreakPoint in general or my writings in particular will know where I’m going next. It is only by appealing to the testimony of God’s self-revelation in the Bible that we can possibly have a sufficient vantage point from which to make judgments about our fellow man. Anything less – cultural custom, personal preference, philosophical inquiry, or pragmatic conclusion – none of these can give us anything other than a shallow solution to a complicated problem.

What do we see of judgment in the Bible? A lot, that’s what. Reading through the Torah, we read of God’s condemnation of human sin again and again. There’s Cain and Abel, Sodom and Gomorrah, the soiled lives of the Patriarchs, the petty whining in Exodus and Numbers, and the frail obedience of Moses himself. The historical books of Joshua and Judges up through Chronicles are little but, well, chronicles of Israel’s repeated sins and God’s equally repeated rebukes of their wayward ways. The writings of the wisdom books warn again and again about dangers of straying from the path of Yahweh onto the roads of our own ideals. Despite their reputation for eschatological emphases, the prophets were far more likely to be found critiquing sins of the then-present than predicting the events of the distant future.

Now, we may say to ourselves that that’s just the Old Testament with its meany, wrathful Father-God. Surely our gentle, gracious brother-Jesus and His forgiving followers of the Early Church wouldn’t do that. Really? Perhaps you should read through the Gospels and Epistles once more to familiarize yourself with the Christ you claim to follow. Jesus was quite keen on laying down the law of God’s justice and promising a harsh awakening for any who found themselves apart from Him on the Last Day. The words of the Apostles, too, were filled with judgments and condemnations. If you were to take out from the Epistles all the instances of moral correction, you’d be left with a thin New Testament, indeed. And don’t even think about a judgment-less Book of Revelation!

So, are the naysayers of Christianity right when they say that the word of God has nothing but doom and gloom for the watching world? Of course not. One glory of our Faith is that it takes sin quite seriously and it insists that these moral corruptions will inevitably receive their comeuppance across the pages of the Bible. But, that by itself would be no more than any other graceless religion of works and self-righteousness. What sets Christianity apart from its competitors is that this judgment is more than matched by the mercy coming from on high.

The same passages marking the wrath of God against human sin also tell us of the gracious provision of God for salvation from our well-earned fate. Adam and Eve are promised a Savior and granted a continued, if temporarily altered, relationship with Him. Cain is invited to disclose his fratricide himself even as God knows what he has done. Moses’ laws against Israel’s sin are accompanied by a clear pathway towards sacrificial forgiveness. The history of Israel and Judah paved the way for great David’s Greater Son, and the writings and prophets pointed to salvation flowing from Zion’s king.

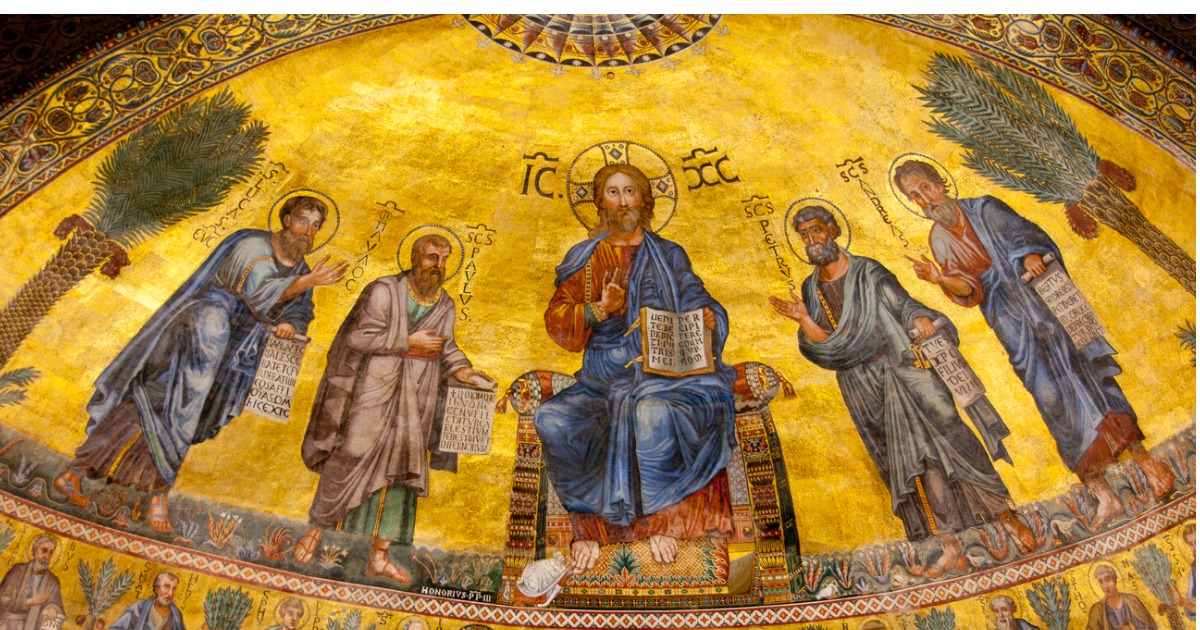

If the Gospels and Epistles declare God’s justified wrath at our sin, they all the more speak of God’s provision of His dear Son. And, if John’s Apocalypse tells of the eternal fire of Hell, it even more reminds us of the wedding banquet for the once sinners made new as the redeemed Bride of Christ. The Christ who sits on the throne of God’s judgment is also the Lamb who was slain for the sake of our salvation.

What the “Judge Not!” crowd misses is that this line of Christ is not the end of His statement. He does indeed say in Matthew, “Judge not,” but, He’s not saying that there is to be no judgment at all, but that our judgments must be made in light of who God is and what He has done for us. As the following verses indicate, Jesus here is reminding us to keep our own sin before our eyes so that we may live out to others that mercy which has been given by Him to us.

Our judging is not to be on the basis of our will and sense of justice, but on His and under which we ourselves stand condemned. It is also not to be with a mind to glory in our supposed righteousness over against our neighbor’s but on account of the mercy which has been poured out on us. With His standards and our sin and His grace and our forgiveness firmly in mind, we will then be in a place to take the log from our eyes before moving on to help our brothers remove the speck from theirs.

The Bible shows us both how to discern what is and is not sinful without descending into the morass of moral relativism and how to proclaim the truth of God’s justice as tempered by His mercy and our own well-deserved humility. By looking to the very regular examples of divine displeasure transmitted through the words of the Prophets and Apostles, we avoid the error on the one side tempting us to leave ethical considerations up in the air. At the same time, by following the pattern of repentance and mercy found throughout the Old and New Testaments, we can approach our fellow sinners with the grace that comes only from those who’ve felt grace themselves.