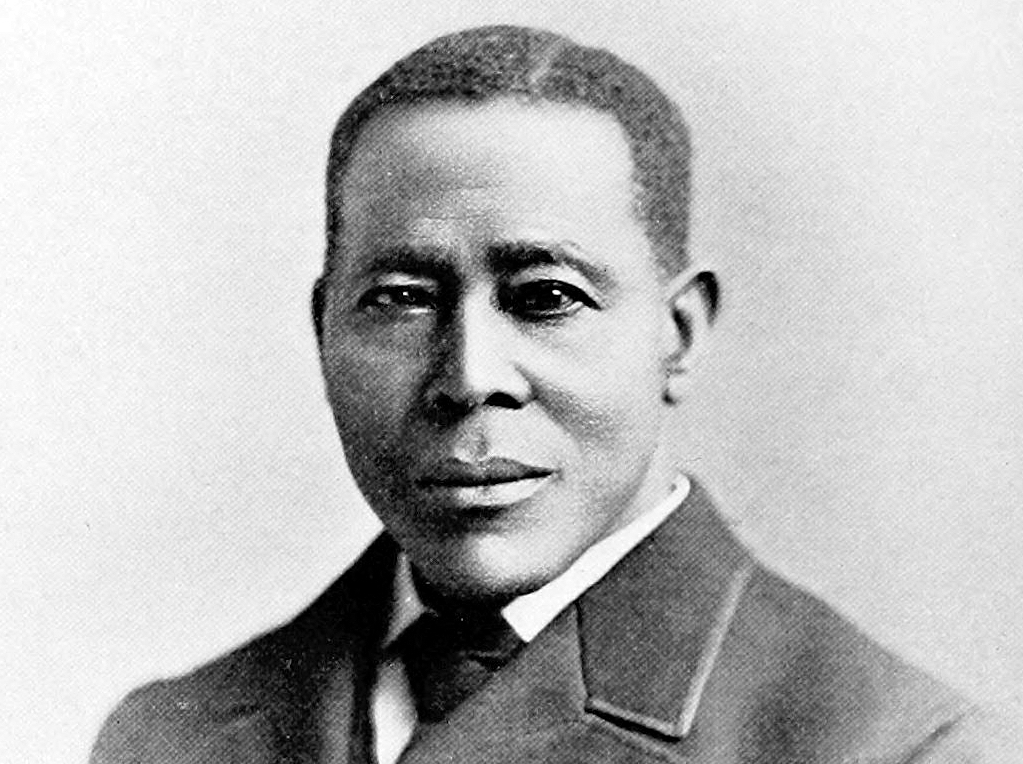

William Still (1821-1902) was born in New Jersey to former slaves from Maryland. His father Levin had purchased his freedom from his master; his mother Sidney (later changed to Charity) escaped from slavery twice. The first time, she tried to bring her four children with her, but they were captured and sent back. Her second attempt was successful, though she was only able to bring two of her children with her. Once in New Jersey, she and her husband had fourteen more children, the youngest of whom was William.

William worked on the family farm and as a woodcutter. He had at best limited opportunities for education, but nonetheless taught himself to read and write by reading everything he could get his hands on.

In 1844, William moved to Philadelphia, where he worked as a janitor. Three years later, he married Letitia George and became a clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. When the Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, the Society formed the Vigilance Committee to help escaped slaves circumvent the law. Still was named chairman of the committee.

In his position as chair of the Vigilance Committee, Still was a central figure in the Underground Railroad. He helped as many as 800 people escape to freedom. In the process, he interviewed everyone who passed through Philadelphia, getting their names, stories, and destinations in a book he kept carefully hidden to help runaway slaves reunite with their families. After the Civil War, Still would use these notes as the basis for The Underground Railroad Records, first published in 1872 and available online from Project Gutenberg. A copy was displayed in 1876 in the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

In conducting these interviews, he met a man named Peter whose stories echoed those of his mother. He realized that Peter was his brother and arranged for him to meet with their mother, from whom Peter had been separated for 42 years. William also learned from Peter that his oldest brother, Levin, Jr., had been whipped to death for visiting his wife without authorization from his master.

William Still worked with agents of the Underground Railroad in Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, New England, and Canada, including Harriet Tubman. He also knew John Brown’s family and sheltered some of his associates after the 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry.

Along with abolitionism, Still worked to advance the place of free and freed blacks in the country. As an elder and founding member of Berean Presbyterian Church, he promoted Sabbath Schools to promote literacy among freed blacks and set up a Mission School in North Philadelphia. In 1859, he published a letter in the newspaper arguing for the desegregation of Philadelphia’s street cars. Not all blacks thought this was a battle worth fighting, so in 1867, he published “A Brief Narrative of the Struggle for the Rights of the Colored People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars.” This, combined with the work of Octavius Valentine Catto, would result in the desegregation of public transportation not just in Philadelphia, but across all of Pennsylvania (1867).

On a national level, Still participated in the Colored Conventions Movement, the precursor to organizations such as the NAACP, which advocated for abolition and a wide range of other issues that affected the Black community.

When the Civil War broke out, Still ran the Post Exchange at Camp William Penn, where black troops were trained for the Union Army.

After the war, Still continued to run a coal and stove business he had started in the war. He also had extensive real estate holdings in Philadelphia and owned stock in the journal The Nation. His success as a businessman led to him becoming a member of the Philadelphia Board of Trade.

Along with his business interests, Still also continued to work to advance the place of freed slaves. He funded and was an officer for the Social and Civic Statistical Association of Philadelphia, which among other responsibilities collected data on freed slaves. He was also active in the Freedman’s Aid Commission and was an officer for the Philadelphia Home for Aged and Infirm Colored Person. In addition to his work for freed slaves, he founded an orphanage for children of black soldiers and sailors and one of the first YMCAs for blacks. Not surprisingly, he was also an advocate for universal suffrage.

In 1902, Still died at home of heart failure. In his obituary, the New York Times described him as “one of the best-educated members of his race, who was known throughout the country as the ‘Father of the Underground Railroad.’”

William Still’s work was undoubtedly motivated in part by his family history. The horrors that he learned about from his parents helped galvanize him to work for abolition, but his interests went far beyond ending slavery. His concern for education, for recognizing the equal dignity of blacks and whites, for caring for the elderly and inform and for widows, all of these were also expressions of his deep Christian faith which led him to help found the Berean Presbyterian Church, to serve there as an elder, and to establish Sabbath Schools and Missions Schools to help educate freed slaves.

Still’s legacy includes his children, each of whom contributed to the black community in Philadelphia in unique ways. His oldest surviving child, Caroline Virginia Matilda Still, was a pioneering female medical doctor, community activist, teacher, and leader. After her husband died, she married the pastor of the Berean Presbyterian Church. His second child, William Wilberforce Still, became a lawyer; his third, Robert George Still, was a journalist and printer; his fourth, Frances Ellen Still, became a kindergarten teacher. His siblings were equally accomplished.

William Still’s descendants continue to hold family reunions annually.

Topics

Apologetics

Bible & Theology

Christian Worldview

Culture/Institutions

History

Religion & Society

Worldview